As we drive down the empty, two-lane highway, the clusters of seaside resorts, tin-roofed homes and finely manicured lawns on this Papua New Guinea island give way to lowland rain forests and palm oil plantations. The telephone lines eventually disappear as do the satellite dishes and, within hours, the team from Nautilus Minerals is on a rutted, dirt road.

Beyond the occasional sprawling logging camps on New Ireland, there are few signs the modern world has touched this part of the Asia-Pacific nation of 600 islands and 800 languages. Largely cut off from the outside world, villagers earn a few dollars each week farming small patches in the forest for sweet potatoes and coconuts and catching the occasional fish from their flimsy, dugout canoes. There is no electricity here, no toilets, no phone services, no cars. Big black pigs are a sign of status and community life revolves around ancient tribal rituals evoked by the spirit houses and shark calling, a dying tradition where villagers shake rattles made of seashells to attract sharks in the Bismarck Sea to the shores before snatching them up with their hands.

Nautilus, an exploration mining company headquartered in Toronto, has come to these villages along the coast to pitch a simple but controversial message: We can make your lives better if you let us mine the seafloor.

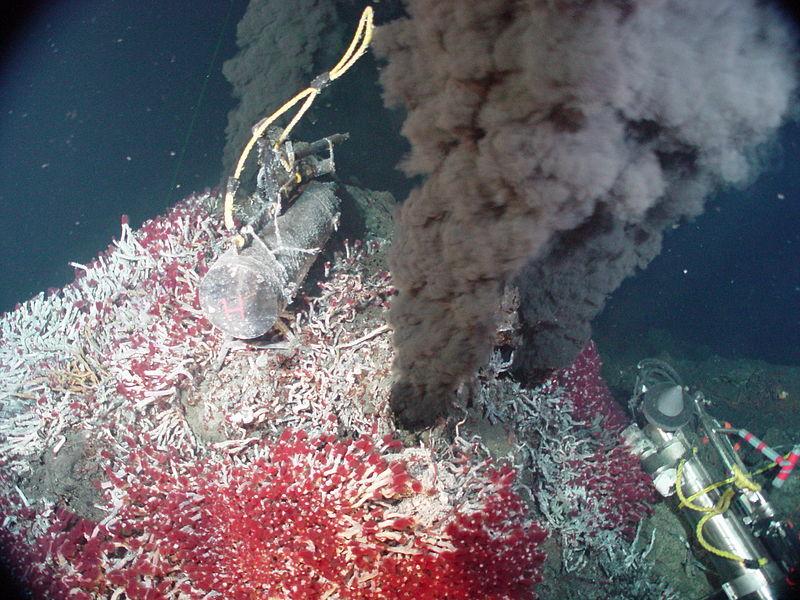

Villagers have embraced offers of new sanitation systems, homes and bridges. But they don’t fully comprehend what Nautilus wants to do starting as early as 2018 at a site 30 kilometers (18.64 miles) off the coast. Located about 1,600 meters (5,200 feet) down, the site is home to a network of hydrothermal vents and near an undersea volcano. It’s a harsh environment where mineral-rich water as hot as 400 degrees Celsius (750 degrees Fahrenheit) pours through the vents, meeting icy cold water and forming the concentrations of gold, copper and other minerals that are 10 times what is found in traditional mines on land.

A race to the bottom of the sea

There is plenty at stake if the company goes ahead with its ambitions plans. A successful project has the potential to set off a modern day gold rush to the seafloor, a prospect that troubles deep-sea scientists and environmentalists who fear the mining could destroy some of the world’s most diverse and poorly understood ecosystems.

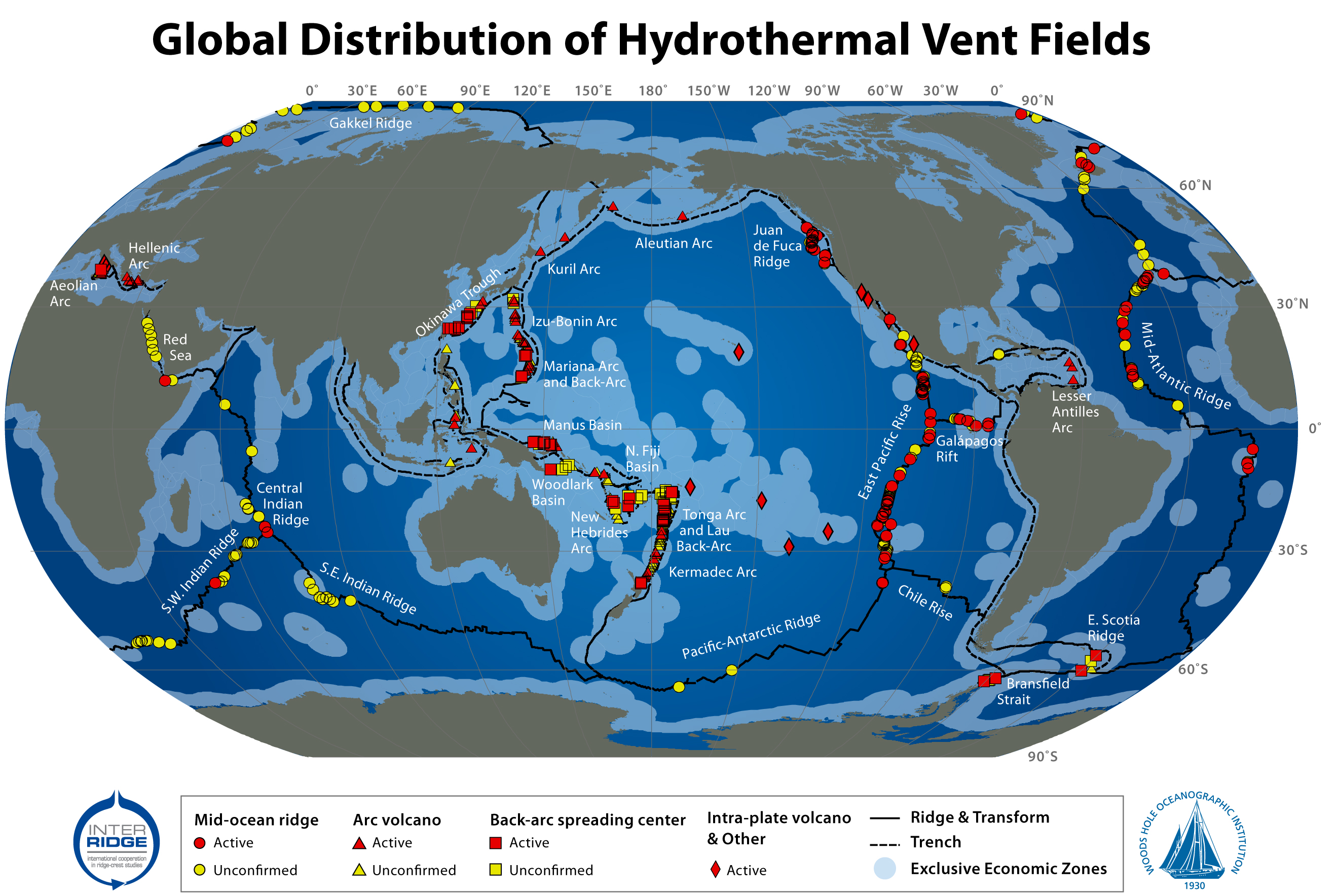

Because of technological advances, difficulties of mining on land and growing demand for minerals like copper, gold and zinc, scores of nations and multinational conglomerates are rushing to lay claim to huge areas of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans — some sites the size of small countries.

Supporters see this as a chance to tap the 70 percent of minerals not on land and transform the way we source these natural resources found in phones, computers, and other electronic devices. Nautilus contends that, by drilling underwater, it can actually shrink its environmental footprint. On land, mining means displacing villages, fouling rivers with mine waste, and lopping off entire mountains to get to the minerals — none of which Nautilus says it will do.

“There are a lot of resources on the seafloor. It’s not inconceivable that ocean mining will be a similar thing in 20 years to what offshore oil and gas is for things like copper, nickel, cobalt, and zinc,” said Nautilus CEO Mike Johnston, whose company is set to take a critical step forward when it tests its underwater mining tools off the coast of Oman in the coming months. “We can’t say we are only going to do this stuff on land … We have to look at the impact man has over the entire planet.”

“If you wipe out large areas of seafloor and cause species extinction, you actually change the future of life on earth, how it evolves, if you do it on a large enough scale.”

The idea of scooping up minerals from the sediments of the world’s oceans has mesmerized adventurers for eons.

Manganese nodules were first discovered in the late 19th century in the Kara Sea during the expedition of the H.M.S. Challenger. But it wasn’t until the 1970s that anyone seriously considered tapping the ocean’s riches of gold, silver, zinc, magnesium, iron, cobalt, and copper.

Scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution discovered the first hydrothermal vents in the Galapagos Rift, more than 2,500 meters (8,202 feet) down in the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of South America. And Lockheed Martin spent three years collecting thousands of samples from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean.

But the sector struggled to gain respect not only from suspicious governments, but the traditional mining industry.

“A lot of people laughed at us,” said Julian Malnic, an Australian exploration geologist who started Nautilus in the 1990s and has been described as the godfather of marine mining.

“One high-profile commentator suggested we were going to use explosives. They don’t even work down there,” he said. “There was a big ignorance factor which everyone was in a hurry to showcase but, in my experience, when you have a new idea, you haven’t got a friend in the world.”

While mining giant Anglo-American at one point had a small stake in Nautilus, none of the other big players have dipped their toes in the water. The sector has mostly dominated by tiny companies with names like Diamond Field International and Neptune Resources that fill their websites with glossy photos and videos of potential sites with a prospector’s air of excitement at the incredible minerals waiting to be mined. No one has yet to do it on a commercially viable scale.

Malnic attributed that to the cautious nature of the mining industry and the boom and bust cycle that comes with the territory. A lack of governance has also hurt efforts to mine in international waters while national governments have become increasingly alarmed over fears of potential pollution from the mining.

There’s reason for caution.

Scientists and environmentalists warn that the technology is unproven and that widespread mining could destroy hundreds, if not thousands of miles of hydrothermal vents systems, undersea mountains, and submarine volcanoes as well as seamounts containing deep sea coral. In doing so, the world could lose scores of species before they are even investigated by scientists as well as potential resources for new classes of drugs, cosmetics, and fuels.

“If you wipe out large areas of seafloor and cause species extinction, you actually change the future of life on earth, how it evolves, if you do it on a large enough scale,” said University of Hawaii’s Craig Smith, a co-author on a paper in Science last year that called for implementing adequate environmental protections for deep sea mining.

“We are doing it on terrestrial environments clearly. So far, we haven’t done it on that scale in the deep sea but there is potential if things aren’t managed,” he added.

“A lot of people are quite shocked to find out about deep sea mining,” said Helen Rosenbaum of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, a coalition of anti-mining NGOs from the South Pacific, Australia and Canada, noting that oceans are already under threat from pollution, overfishing and climate change.

“The general public aren’t aware of it,” she said. “This is another way in which our oceans are being hammered. They are already predicted to fail ecologically over the next couple of decades if we continue business as usual with the impacts they are already experiencing — let alone this new one.”

One company’s experiment

The companies themselves have had their own challenges, none more so than Nautilus.

Malnic first secured rights to the site off PNG’s New Ireland in 1997 after attending a presentation at Australia’s premier scientific institution, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, on the discovery of seafloor massive sulfides at the bottom of the Bismarck Sea.

He did what any good mining prospector would do. He reconstructed the seafloor maps and quickly secured exploration licenses in PNG for Solwara 1 and another site in 1997. From there, he started scouring the South Pacific for other sites, recognizing that most were within the 200-mile economic exclusion zone of these island nations.

“Here were these beautiful high grade sulfides coming out of the box,” said Malnic, recalling the lecture when the ore from the Bismarck Sea was put on display.

“I could see immediately the great potential,” he said. “I’m still totally excited. This is the frontier for copper and zinc production in the future.”

The excitement, however, would give way to a decade or more of frustration and delays.

Traditional mining companies wouldn’t touch the project and efforts to raise capital came up against, what Malnic calls, “the second half of a nuclear winter of zero capital available for exploration and mineral projects.” But the 1997-98 economic crisis was just beginning.

It would be another five years before the crisis eased and a metals market, driven by the emergence of the resource-hungry Chinese economy, started recovering. Soon enough, the suitors started knocking on Nautilus’ doors.

Yet even as the financing began flowing, the company struggled. Malnic left in 2006 and the company went through two more CEOs before settling on Johnston. Its stock, which debuted on the Toronto Stock Exchange, reached a high of $4.38 in 2008 before falling rapidly to 14 cents.

At the same time, the company learned just how hard it can be to operate in a tribal society where minerals like gold and copper are abundant — but so is corruption, angry landowners, and activists increasingly fearful about the environmental damage caused by mining.

It didn’t help that the company was arriving on the back of several high profile mining disasters in PNG, including the spillage of tens of millions tons of waste from the Ok Tedi gold and copper mine that polluted a river on the island that tens of thousands depend on for water.

“They spent $400 million and didn’t come up with a mine,” said Malnic — money he claims mostly went to scientific studies and other fieldwork. “It was just catastrophic. They could have been mining twice over for that much and they came away with a bunch of studies and some contracts. It’s unforgivable.”

Nautilus and the PNG government also fell out over the government’s failure to contribute its share of developing cost to the project, forcing the dispute into court and almost killing the project. The unstable government — at one point featuring two, dueling prime ministers — didn’t help.

But the two sides resolved their differences and the government got a stake in the project’s potentially lucrative intellectual property. The settlement has the easy-going Johnston — a New Zealander who often favors a dress shirt and jeans to a suit and throws in the occasional cuss word when making a point — more bullish than he has been in years.

“When we were in the dispute with the government, a lot of people were sitting on the sidelines watching,” said Johnston, who has been credited with repairing relations between the two sides and has been known to spend days in villages counter rumors and allegations against the company. “Now that the dispute is finished, there is a lot of interest again. A lot people want to see us go a little bit further.

A rush to get a piece of the action

Some of the greatest interest in seabed mining in the past few years has been around the Clarion Clipperton zone, an area about 80 percent the size of the contiguous United States in the Pacific between Mexico and Hawaii. By some estimates, it contains an estimated 62 billion tons of nickel, copper and cobalt in bowling ball-sized nuggets that litter the seafloor.

Because these are in international waters, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a tiny U.N.-affiliated body with offices in Jamaica, is tasked with issuing licenses to explore these and other areas. Just in the past four years through 2015, the number of exploration license has jumped from 7 in 2006, to 27 in an area that encompasses 1.4 million square kilometers.

“Right now, we don’t know what will happen when mining starts. We do know the animals living at the sites that are mined will be eradicated but we don’t know whether or how quickly those communities can become reestablished.”

Increasingly, companies backed by Russia, Japan, and China, as well as tiny island nations like Tonga and Kiribati, are taking out permits to explore huge sections of the area. One of the biggest private firms, UK Seabed Resources — a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin UK — is prospecting for minerals in a 22,300 square mile area of the Clarion Clipperton zone and says that could bring $60 billion to the UK economy over a 30-year period.

“What we have seen in the past few years is a huge explosion in activity,” said Michael Lodge, the deputy to the ISA’s secretary-general and legal counsel.

“It shows an increasing interest in the sector and prospects for the sector. There are two or three things converging — developments in technology that makes it more realistic and the cost of traditional mineral projects is becoming more expensive and difficult to source,” he said. “You are reaching a point of equilibrium. Although seabed mining is terribly expensive and very high risk, it’s competitive with the cost of setting up a source on land. Also, people are looking for long-term sources of very high grade minerals.”

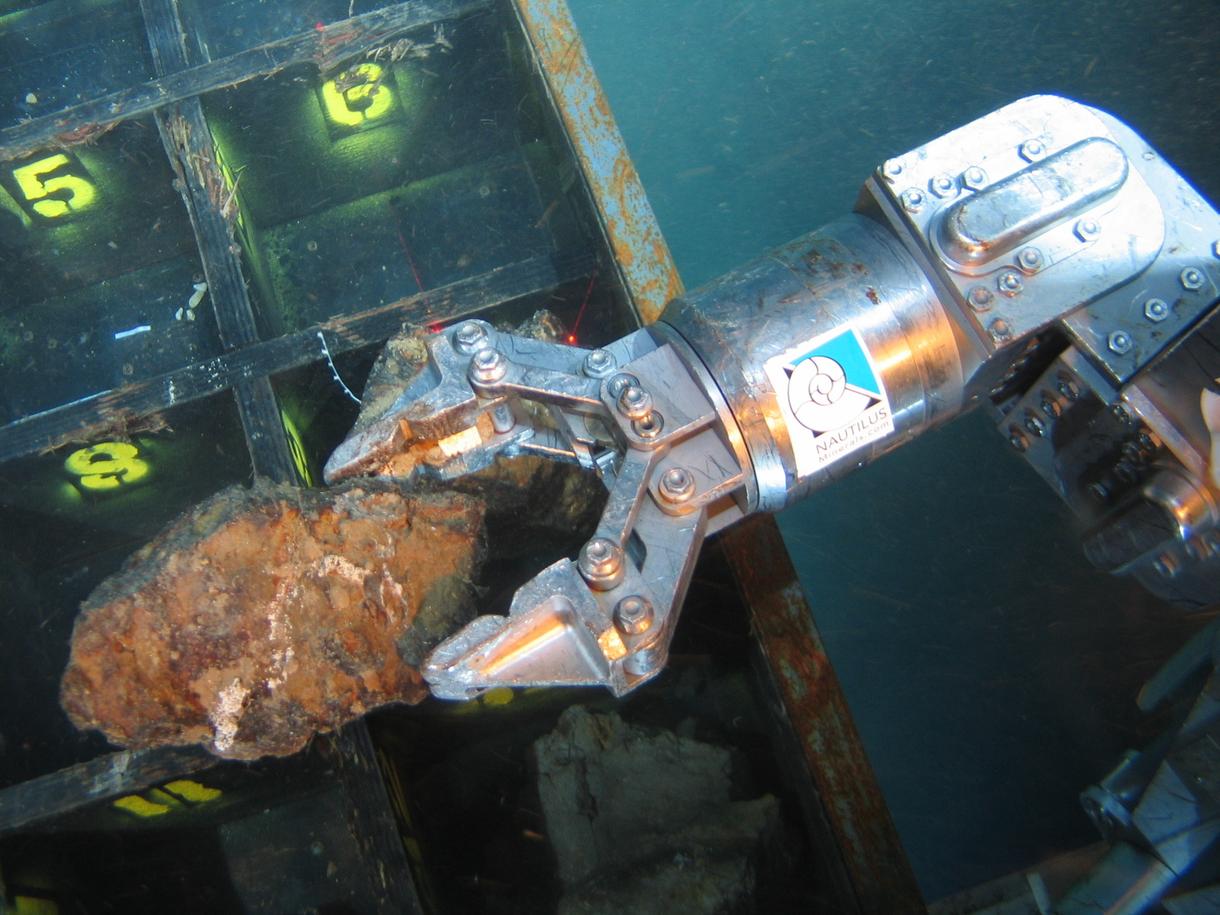

For now, much of the action is on building the mining equipment in places like the United States and United Kingdom that has been adapted from technology already in use in the oil and gas, dredging and coal industries. Once it starts, the plans call for lowering several remote-controlled, robotic cutting machines to the seafloor. Mineral-laced rocks will be carved from the seafloor and sent up through riser pipes and lifting systems to a tanker-like ship waiting on the surface. The excess water from the ore will be returned to the sea bottom and the minerals sent to China’s state-owned Tongling Nonferrous Metals Group.

More than just minerals in the deep

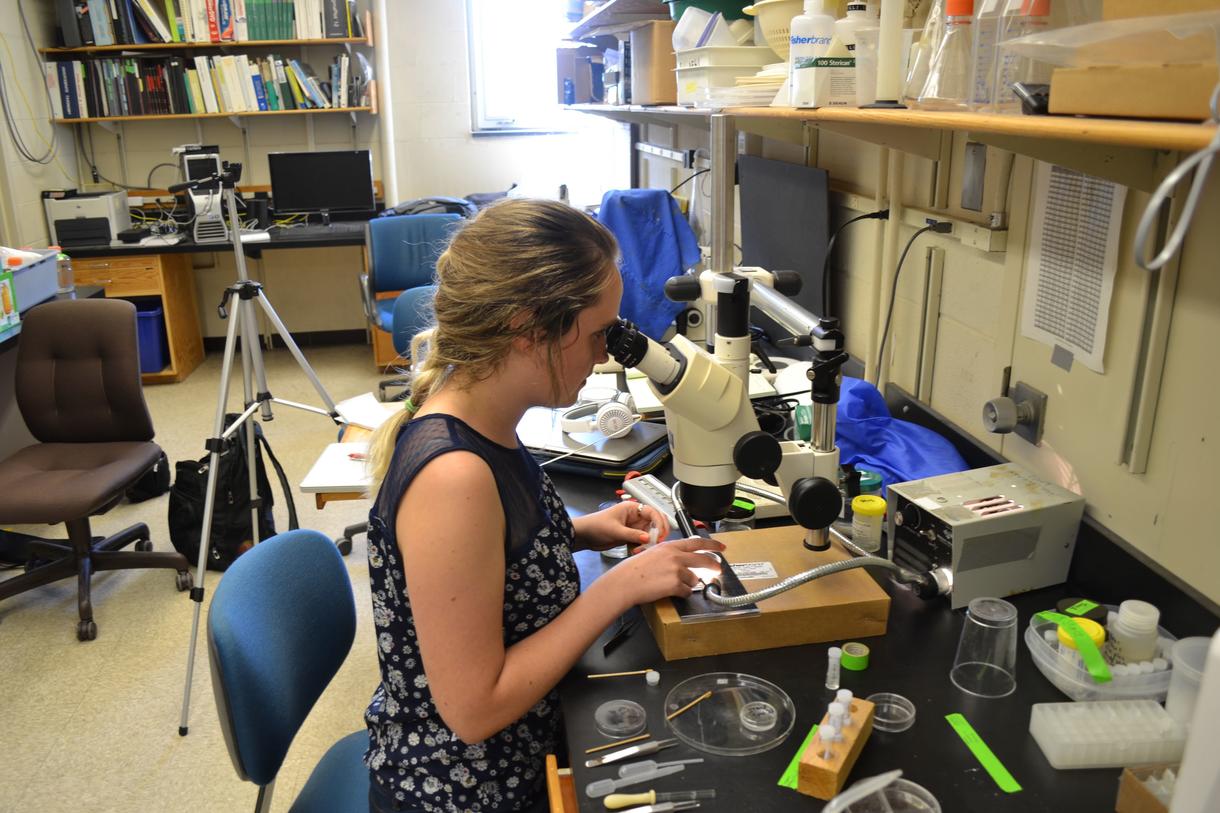

Stace Beaulieu, a biological oceanographer at Woods Hole who has spent the past 20 years studying the biodiversity and abundance of life on the ocean’s seafloor, has watched this growing interest in deep sea mining warily.

“Right now, we don’t know what will happen when mining starts,” she said. “We do know the animals living at the sites that are mined will be eradicated but we don’t know whether or how quickly those communities can become reestablished. That uncertainty is why a lot of deep-sea scientists have great concern about mining.”

Like the other scientists in Lauren Mullineaux’s lab at Woods Hole who study the world’s hydrothermal vents and other seafloor habitats, the wiry and energetic Beaulieu is passionate about the deep sea. If she isn’t gearing up for a weeks-long journey on a research vessel, the avid runner and biker is hunkered down in her tiny, crowded lab. It’s filled with mementos of past trips including nets and foot-long bottles containing red-tipped tube worms and dozens of preserved samples in ethanol. Just down the road from the lab is the tranquil, ocean-side community of Woods Hole, with its lobster shack, organic coffee shops, and a marina that looks out on Vineyard Sound.

Unlike other scientists who may study the seafloor’s large creatures like clams, crabs, or tubeworms, Beaulieu and her lab-mates are more concerned with the macro fauna — the deep sea invertebrate communities including snails, smaller worms, and crustaceans. They are among the most diverse animals on the seafloor and play a critical role in the food web.

“We want to find early life stages of animals that live on the sea floor,” she said, holding up a pinky-sized tube containing samples that came from a 2010 trip to the Mariana Arc and the site of an erupting submarine volcano. “Now, they are mostly transparent and white. In life, they have beautiful colors. They are much more beautiful alive.”

When the first hydrothermal vents were discovered in 1977, scientists were shocked with what they saw. Instead of flat, featureless desert, they found vents teaming with tubeworms, mussels, clams, crabs, snails and shrimp.

“The thing that caught everyone’s attention when they first discovered the vents was the large numbers and large volumes and large biomass in the animals and communities,” said Mullineaux, who has been on 30 cruises and made nearly 40 dives as part of her work studying the dispersal of larvae of benthic invertebrates and their return to the sea floor.

“This was a huge surprise because, at that time, we thought deep sea communities were being fed by small particles that drifted down from the sea surface where they were produce by photosynthesis,” she said. “Clearly, that production by photosynthesis was not sufficient to fuel these amazing robust communities that we found on the seafloor.”

Mullineaux said they realized something else entirely was happening — a process called chemosynthesis, where microbes convert chemicals dissolved in the vent fluids into usable energy.

Since then, hundreds of vents have been discovered and thousands more are believed out there. Many are home to strange creatures that go to unusual lengths to thrive in these toxic environments. One of the strangest is a family of tubeworms calledSiboglinidae that have no mouth or gut and “get all their sustenance by these endosymbionic microbes that live inside them.”

In the Clarion Clipperton zone, scientists are just beginning to explore its rolling seafloors which have higher diversity than vents, but are mostly dominated by tiny creatures living in the sediment.

“I’m just working on the data now and the samples are some of the most diverse, have some of the highest species diversity of samples ever collected from the sea floor,” Smith said, who is doing baseline surveys for UK Seabed Resources, noting that each of these quarter square meter samples contain upwards of 60 species of polychaete worms, crustaceans, mollusks and snails.

“These are animals living in the sediment that you don’t normally see,” he said. “Every sample we bring up has dozens of new species. In fact, 80 percent to 90 percent of the animals, the species we bring up are new to science. People get all excited about the discovery of a new species in a terrestrial environment. We are bringing up hundreds of them on every cruise.”

To mine or not to mine

When he is not at sea, Smith is part of a group of scientists helping to shape environmental measures being drawn up by ISA. Unlike environmentalists who want an all-out ban on deep sea mining, Smith and others are more pragmatic, arguing mining will happen at some point, so they are trying to determine where it can and can’t go.

“I think slowing down is an excellent idea,” said Lisa Levin, who is with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and who co-founded the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative, which among other things advises on the use of resources in the deep ocean. “We should be slowing down and collecting relevant information that is needed to make a decision. In most cases, I don’t think we have it. If a moratorium is a way to slow down, that works.”

What makes drawing up these regulations challenging, Levin said, is that each type of mining would take place in ecosystems that “operate on different time and space scales.”

“Some are small and patchy. Some are heavily disturbed and recover quickly. Some are vast and processes are very slow. Some animals live for hundred or thousands of years and others live for 10 years,” Levin said. “So each system requires a careful look at the dynamics and the composition and the vulnerability of those ecosystems to mining impacts.”

Duke University’s Cindy Lee Van Dover and other scientists have suggested staggering the mining activity in a certain area, as well as limiting mining to inactive vents that could be easier to mine, but also less important environmentally. Companies should also consider setting aside areas within their sites so the mining impacts can be evaluated and relocating species deemed ecologically significant.

But with no past experience to go on, it can be a struggle for scientists to know where to draw the line on where mining can take place . Nautilus, for example, may be starting with Solwara I, but it has far greater ambitions.

It has more than 500,000 square kilometers (310,686 miles) of exploration acreage in the Western Pacific, including some 19 sites in the Bismarck. It also has sites in Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, as well as international waters in the eastern Pacific.

“The cumulative impacts for any of the mining scenario is what is really critical,” Van Dover said. “If Nautilus only mines one site, no big deal. If they mine two sites, we don’t know. Three sites, we don’t know where the tipping is, where does it matter in terms of the connectivity of the animals and when will you lose not just species diversity but ecosystem function and services.”

Short of wiping out the tube worms, bivalves, and gastropods living around the Nautilus vents, even mining on a small scale has the potential for disaster. There also are concerns the project could change the chemistry near the vent sites and produce toxic plumes that could bury organism and clog the feeding apparatus of sea creatures.

“There is no way to know where the plume is going to go until they make it,” said Van Dover, who has in the past studied the Nautilus site. “We haven’t seen the mining tools in action. We don’t know how much sediment they are going to move.”

Islanders — Guinea pigs or pioneers?

Opponents, who for several years have waged a global campaign against the Nautilus project, paint a far grimmer picture. In a series of detailed reports, they warn that storms, spills, or technical snafus could spark a disaster that would wipe out fisheries, destroy some of the world’s most diverse coral reefs, and pollute the waters of coastal communities across the South Pacific.

“People are afraid because they know there will be damage on our reefs, affecting our marine life,” said David Bekeman, a primary school teacher in Komalu, a village near the mine site. “Nautilus is telling us there will be no damage. We definitely know there will damage but we don’t have the power to stop anyone from doing anything in the sea.”

While Nautilus is building latrines and handing out textbooks, a loose-knit and cash-strapped group of opponents that includes young activists, school teachers, church leaders, and a retired army colonel have tried to raise awareness in the international community and the impacted villages.

“We aren’t anti-development but we are saying to the government it must act responsibly,” said William Bartley, a retired colonel who opposed the project. “Papua New Guinea is not ready for this. They have not even told us what actions they would take supposing an environmental disaster does occur.”

Johnston dismisses the criticism from “outside groups” that “don’t want this to happen” and insists his project will only cause harm to the fauna at the mine site. “I’ve heard a lot of that stuff and a lot of that is misinformation. I’ve heard the one about poisoning the water. I don’t even know where that comes from,” Johnston said. “It makes me quite angry when I see outside NGOs telling villagers that is going to happen because the river is really important to them.”

In these villages of mostly bamboo huts surrounded by idyllic views of the rocky coastline, the villagers are left with competing versions of the future. Will mining activities bring development or destruction to their lands?

The company is also a regular presence in the villages, conducting surveys and laying the groundwork for its first development projects. Like so many mining companies, they are often tasked with doing the job of the government — which appears to have largely left these remote villagers to fend for themselves. And with little investment until now, even the most basic things need the company’s attention.

The schools, for example, lack textbooks, water and toilets — forcing children to relieve themselves in rivers and exposing girls to sexual harassment and even rape. The classrooms have almost nothing beyond a chalkboard. Any students must walk hours, if not an entire day, to reach them.

The medical clinics — also hours away by foot — are often shuttered due to a lack of medicine. As a result, some of the most common causes of death in the villages are childbirth as well as treatable diseases like malaria and respiratory ailments, according to surveys done by Nautilus.

In the villages, there are no shops or any commercial activity, since the mountain roads are often impassable during heavy rains. The only sign of tourism is an abandoned guest house built by an Israeli adventurer. Most farmers, meanwhile, have abandoned cash crops like coconuts in favor of staples like yams, since it can be such a challenge to get them to markets.

The talk from Nautilus of fighting diseases and easing hunger resonates with villagers like Jenny Gebo, who in her tattered blouse and skirt laments how it takes her all day just to gather enough vegetables to cook the evening meal. Standing over a smoky fire, she was preparing a traditional Papuan meal called mumu, in which the food is soaked in coconut, wrapped in banana leaves, and cooked over a pit.

“We are finding it hard now to help our families,” said Gebo, a mother of four from Komalu, one of the closest villages to the mining site. “The mining could help our families. But if the mining comes and the seas get polluted, we won’t get the fresh fish.”

Out in the forest a few miles from the village, Henry Tabu was tending to fires he had lit to clear his land. As the flames reached several feet in the air and the smoke seared his eyes, Tabu, bare-chested and wearing a cross, recalled how he didn’t earn enough money to send all his five children to school. He complained that his tiny plot barely was enough to feed his family.

“We are trying our best to look after our family,” Tabu said, as his children stoked the fire and a puppy whined in the background. “The project will come. It will help in some ways to make people live better. Maybe it will help me look after my family.”

This story originally appeared on VICE NEWS and was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.