Mebai Warusam sits under his stilt-supported house, facing the Pacific Ocean’s turquoise waters lapping 50 metres from his front gate. At 91, born and raised on the island of Saibai in the Torres Strait, he is an elder visitors and locals turn to for knowledge.

A few years ago, he says, researchers from down south travelled to Saibai. “They said, ‘If water comes right through this island, what you will do?’ I said, ‘I will never move from this island.’” “I will jump on my boat, tie that rope on a wongai tree. I will live here; I will die here.”

Patimah Waia, a teacher, underlines the point. “People are now realising that global warming [is happening] and water is rising and Saibai is low … some people, even though they realise its global warming that causes the water to rise, are so much in love with the place that they don’t want to leave.”

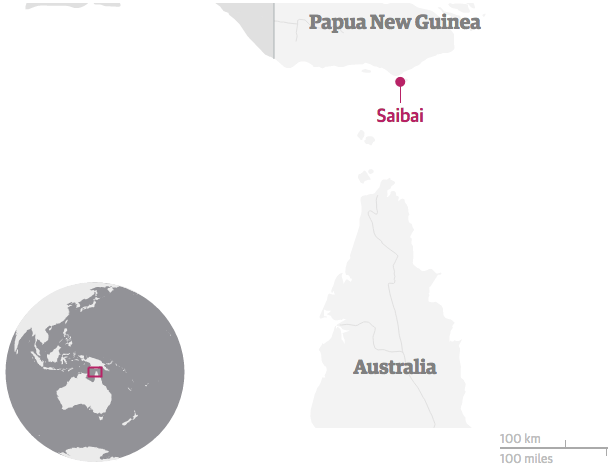

Saibai is one of more than 200 islands and coral cays that make up the Torres Strait, the archipelago straddling the waters between the northernmost tip of mainland Australia and Papua New Guinea. Eighteen of the strait’s islands are inhabited. For most of the island communities here, the impact of climate change is a daily reality. Coastal erosion, rising sea levels, worsening yearly floods, frightening king tides and drought are all regular occurrences.

As Australia negotiates new global climate targets with the world’s decision-makers in Paris, many in the Torres Strait hope for increased attention to the culturally and environmentally unique islands slowly sinking in Australia’s backyard. Saibai and the rest of the Torres Strait islands are officially part of Queensland.

A climate report published by the Torres Strait regional authority, the local Indigenous body, found sea levels in the region rose by 6mm each year from 1993 to 2010, compared with a global average of 3.22mm. The same report said the mean rate of sea level rise since the middle of the 19th century has been higher than the mean rate in the previous two millennia. For the seafaring Torres Strait islanders, the rise can mean profound lifestyle changes.

“Our word for home is the same as an island,” says Joseph Elu, chairman of the Torres Strait regional authority. “If that is lost, people will have nothing left. The weather patterns have changed. We usually get storms this time of the year but we haven’t had one yet.”

When the storms do come, so do the tides. For low-lying islands such as Saibai and Boigu in the far north of the strait, this means annual floods and inundation.

People here are no strangers to unexpected weather events. In the years after the second world war, a water spout inundated Saibai, drowning crops and filling wells with salt water. Fearing a repeat, in 1947 several families from the island relocated to Cape York on the Australian mainland and established villages, known today as Bamaga and Seisia.

Elu says his family was among those who left Saibai. Now extreme weather has become commonplace, he says. “What happened there on the one instance that water spout came down is now happening twice or three times a year in the full moon high tide months of December, January and February.”

Normally, rain mitigates the impact of seawater inundation by washing the soil of salt, enabling crops to grow. But this year the drought that has also hit much of Queensland has brought water restrictions to including Saibai and Boigu – and fears for what might happen if it doesn’t rain soon.

The demand for resources on Saibai, particularly fresh water, is heightened by pressure from the coastal villages in adjacent Papua New Guinea, says John Rainbird, a climate specialist at the Torres Strait regional authority.

Under a treaty, communities from the two countries trade and interact with each other daily. Now the villages in Papua New Guinea have run low on water and villagers regularly come over to Saibai seeking basic services.

For community leaders such as Keri Akiba, the increased pressure stokes fears. “I’m really worried. Sometimes I’m sitting, just thinking that in 20 to 50 years all this place will be under water, the way it’s going,” he says. “It will be under the water most of the time, and then the sicknesses and diseases that will obviously come out of that.”

Rainbird was one of the architects of the Torres Strait’s climate strategy. The focus is on planning and resilience. Of course, planning is made harder by the fact nobody knows for sure just how fast the changes will happen. But one thing is sure, he says. “Anywhere that you have a problem, climate change will only make that problem worse.”

The Torres Strait, says Rainbird, is on the front line of climate change in Australia. Now is the time to prepare. “In 30 years’ time, the Gold Coast, Sydney and Melbourne will all be dealing with sea level impact in some way, competing for limited government resources,” Rainbird says. “We need to get in early while we can.”

The Torres Strait’s population pales in comparison with the coastal areas in Australia’s south. Government statistics show about 8,700 people live in the Torres Strait, while more than 40,000 Torres Strait islanders live in other parts of Australia. Initially climate change will affect only a few hundred islanders, in particular on the low-lying islands of Saibai, Boigu, Masig, Warraber and Iama.

Do Torres Strait islanders feel they have been forgotten? Elu smiles at the question, pointing out there is a book calling the Torres Strait islands the “forgotten isles”. Elu says the previous government dedicated funds to helping Pacific island nations such as Kiribati deal with the threat of rising sea levels, as Torres Strait islanders looked on. “Islands are sinking here,” he says.

Within the Torres Strait, some feel they’ve been left to fend for themselves. Explaining the impact of sea level rise on Poruma Island, councillor Phillemon Mosby says despite media and government interest, little has been done to tackle the changes. “Does anybody out there know about us, does anybody care?”

On the central coral cay islands of which Poruma is one, the issue is erosion rather than of salt water inundation. Large chunks of the island get swept away by tides. In some cases, the sand migrates elsewhere on the island and builds new plateaus.

In remote areas, climate adaptation and building resilient communities is expensive, and although Indigenous people have traditional ways of recording and adapting to changes in weather, the competition for limited funds is fierce. Although $26m has been set aside for building seawalls on Saibai, it is estimated that will barely cover more than half the front part of the island. On mud islands such as Saibai, water also comes in from the wetlands in the middle and the back, leaving the islanders with a narrow strip of land between the ocean and the swamp.

Many locals also recognise that putting up seawalls is only a temporary solution. “You don’t want to scare the hell out of people but it’s also important that people are informed,” says Rainbird.

Mosby says: “When we hear warnings of tsunami and all that, people do get stressed about it. Mentally it is affecting our people.”

Being informed also means discussing the worst-case scenarios, including leaving the islands. But Saibai leader Keri Akiba says leaving is not an option his community is willing to consider. Leaving the island behind would mean abandoning culture, heritage and relatives buried here.

Akiba adds: “I hope the perpetrator governments that have got the coal power houses would decrease them so that the low-lying areas, the islands like Saibai, or even in the Pacific that we’ve seen in the news, get a little bit more time to enjoy their heritage and where they were born.”

This story originally appeared in The Guardian and was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.