JIMIONE Paki was 71 when he decided to do something for his children and grandchildren.

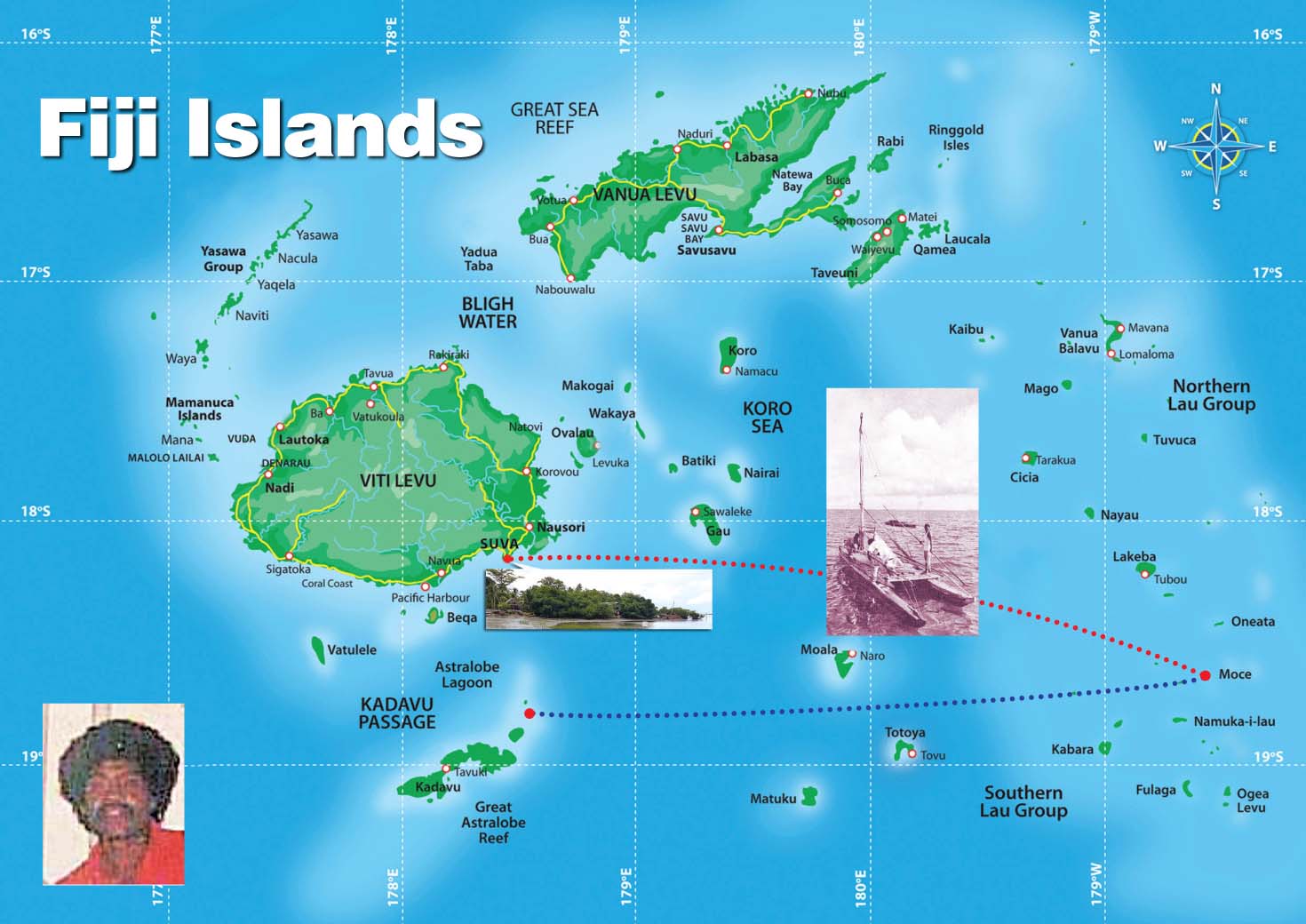

His children had moved from the island of Moce in Lau to the city to study and work.

Life was tough on the island. His village of Korotolu was fast emptying. The young were moving to VitiLevu, leaving the elderly like him behind in their search for a better life in the fast-growing capital Suva.

It was in the ‘80s and early ’90s and the people of Lau were the leaders in Fiji’s urban drift.

The furthest islands in the Fiji arhipelego, Lau was investing in the education of its children and quality education was then only available were development was taking place.

Jimione’s wife was from the neighbouring island of Ogea and they had 16 children. He sent some of them to the mainland on VitiLevu where they were educated and found work.

But with no home of their own in Suva, he worked hard to secure a place that his kin of Korotolu could call their own.

His prayer was answered in 1991 when the then Tui Suva, on whose ancestral land the capital was built, allowed them to settle among the mangroves along the Suva Peninsula, close to the University of the South Pacific’s Maritime Studies.

Named Korova, the swampland became home for his children, grandchildren and extended families.

From Korova, Jimione could see cruise liners sail into the harbour and the flurry of activities tourists brought to the other side of the peninsula.

A DREAM IS BORN

It was the year that he decided he’d return to Lau and sail back on a drua, a traditional Fijian canoe in the hope that it would help them start a business in their new-found home by the sea.

The old man was not only in love with the drua but also with the camakau (single-hulled canoes) that the people of Ogea built.

And he prided himself at sailing them. He believed that promoting their culture through tourism would help them save a way of life that was fast disappearing in the islands.

His eldest son, SemitiCama said his father always told them that the people of Fulaga and Ogea were the best canoe craftsmen in Lau but the people of Moce were the better sailors.

“When we were small on the island, he would always encourage and teach us the right way to sail using the wind, the stars and the pattern of the waves,” he said.

“My father believed that through the venture we would not only benefit financially but save ancient knowledge and technology that scientists believe is apt for our needs in today’s world.”

His mother’s relatives on Ogea built their drua and camakau from vesi trees (Intsiabijuga, a hardwood found on many islands of Melanesia, Micronesia,Polynesia and Southeast Asia that grows up to 40m tall and is one of the most highly valued trees in the region, both in terms of its traditional cultural importance and value for commercial timber) – for fishing and travel between the islands.

“We were fortunate that the then Tui Suva gave us a place to place.

“He came here and told us to fill the swamp and build our houses and we have been here since.

“Our people had big plans to turn this foreshore settlement into a traditional village attraction for the many tourists who were visiting Suva,

One of his relatives built a model of the village and Paki gave inspiration to Korova’s dream when he sailed the drua from Moce.

He was accompanied by his son, MetuiselaBiuvakaloloma, on a camakau.

The purpose of the camakau was to ensure that his descendants at Korova would not lose their sailing knowledge while living in the capital.

When the drua and camakau arrived at Korova, Biuvakaloloma decided he would own a business sailing tourists around the harbour on the traditional canoes.

“My brother was one of our parents’ favourite,” Cama said.

“When my father sailed the drua to Suva, Metuisela followed in the camakau.”

That historic vogage changed life for Biuvakaloloma. His wife, also of Korotolu in Moce, gave birth to a son that same year.

They named him FulunaTuiMoce after the first recorded chief of Moce.

Cama said his younger brother was full of energy.

“He had a big heart and big dreams and a streak of rebellion.

TRADITIONAL PROTOCOL

When Biuvakaloloma decided to return to Moce to bring back another drua start his tourism venture in 1993, he was told to wait until the sea was cleared for travel.

A taboo had been imposed in the waters of the Tovata confederacy following the death of Fiji’s then President, the TuiCakau, Ratu Sir PenaiaGanilau, at the Walter Reed Hospital in the US on Decembers16, 1993.

RatuPenaia was head of the TOvata confederacy of which the islands of Lau are part of.

As part of the traditional protocol and sign of respect for the paramount chief of Cakaudrove, mariners were warned to stay clear while the chiefly cortege travelled to Somosomo in Taveuni, Fiji’s fourth largest island in the north.

On the night of December 28, 1993, Biuvakaloloma defied the advice and set sail for Suva to start his drua cruise business.

It was mistake, he would never learn from.

The next morning the government vessel, Tovata, left Suva carrying the fallen chief.

The Fiji Times reported that it was only fitting that a school of sharksappeared suddenly to accompany the funeral flotilla that Wednesday.

The event was witnessed by the thousands of mourners who came to bid farewell to the chief on his final journey home.

The sharks -regarded as the custodians of the TuiCakau resurfaced during the ceremonial 21-gun salute in front of the Tovuto, which carried the formerpresident of Fiji’s coffin to Somosomo where he was laid to rest.

The Fiji Times reported that the seas were rough as the Tovuto sailed towards Tavenuni.

Cama said from the acounts of relatives on Moce and Moala, another island about 169km away towards Suva, the sea conditions were the same.

It was the last place from where Biuvakaloloma was seen.

No one knows what happened to him that day.

Cama and Biuvakaloloma’s son, Fuluna, who was only three at that time, believe his defiance of traditional protocol cost him his life.

“We can only imagine what happened to my brother. He could have fallen off the drua because of the bad weather conditions or something worse could have happened,” Cama, now 73, said.

“Maybe the sharks attacked him.”

Fuluna said his father breached rules that indigenous Fijians should have observed.

“When there’s a taboo at sea, we should always observe that. The land and ocean are inter-linked.”

“Our forefethares respected that and our people have always relied on the ocean for theirs survival.

“Our stories revolve around it, our life too. The ocean sustains us and gives us life and we should always link them because they always have been.”

Several days later, the family at Korova heard a report that a canoe had beached at Buliya, an island off the Kadavumainland, 313km from Moce.

Some of Biuvakaloloma’s brothers later tried to travel to Kadavu to retrieve the drua but their father advised against it.

“My father said the drua was his coffin and for us to let it be at Buliya.”

According to MarikaBiaukula of Buliya, the canoe was pulled to the village from where it had beached. Overthe years, it disintegrated. All that’s left of it today is part of the bow.

Being blessed with many sons, Paki never lost hope of the dream he shared with his lost son.

Cama moved to Korova in 1996 and helped his father teach the younger generation

The children at the swampland continued to learn the art of sailing the drua and camakau.

The drua and camakau he brought from Moce in 1991 had started to rot.

Cama kept their tradition alive and built several more camakau at Korova the following years.

Eleven years after he lost his son at sea, Paki decided to return to Lau and return with another drua to Suva.

But the ghosts of 1993 returned to haunt the family.

CURSE OF THE CANOE FAMILY

After his son disappeared at seas, life was never the same for Jimione Paki.

He was restless. All that the old man had worked for and dreamt of for his children and grandchildren was disintegrating before him. The death of MetuiselaBiuvakaloloma – believed to be linked to his defance of traditional protocol and taboo of waters in and around Cakaudrove when the body of former Fiji president and andTuiCakau Sir PenaiaGanilau in 1993 was taken by sea to Somosomo in 1993 -took the wind out of his sails.

Korova, the swampland settlement where he had moved to from Korotolu in Moce in Lau with his children in 1991, remained unchanged.

Paki’s kin there had big dreams of turning it into a traditional Fijian village and showcasing it as part of a cruise business.

The was the reason BIuvakaloloma returned to Moce.

Eleven years after that mission failed, Paki told his children he would sail again to Lau and bring back another drua. He was 86.

SemitiCama, his eldest son, said the old man Paki ws adamant about the voyage despite their concerns for his age and health.

This time, he planned to go to Ogea, his wife’s island and collect a newly-builtdrua.

“Our mother’s people are skilled boatbuilders and my father wanted to come back on one from there,” he said.

“It was hard to stop him at the age. Of course we worried about him. But like Metuisela, when we told him not to sail at that time, he was stubborn.”

Paki was last seen sailing past Moala in 2006, the same place his son was last seen on his drua in 1993.

Where he fell off tedrua, or suffered some other fate, the family will never know.

“WE sometimes think it had something to do with my brother’s breach of the taboo to sail in the waters of the Tovata confederacy (of which his island Moce is part of).

“We will just never know.

“The curse of the land is a difficult thing to understand and deal with.

“We lost our beloved brother and then our old man in exactly the same way.

Only this time the drua he sailed on from Ogea was never found.”

FulunaTuimoce, Biuvakaloloma’s son, was only 16 when Paki met his fate.

As a teenager growing up under the old man’s wings aafther the death of hia father, losing Paki was an emotional and painful experience.

The ocean had taken away two people that he ghad truly loved.

And there was nothing he could he could to do to ease his anger at the waves that rushed up to his home in the mangroves of Korova, next to the Unirversity of the South Paciific’s School of Maritime Studies at Laucala Bay in Suva.

His life was one of turmoil and frustration.

His only connection with his father and granfther were pictures – of him, of a model of threir dream village an the drua cruise business.

Ironcally, his only solace was the ocean.

Once day, when his heart felt heavy, he jumped on his camakau and let the wind push him into the harbour.

There, he’d dpend hours fishing, thinking and contemplating the future.

“I love the ocean. As much as I often looked at it with anger qhen I think of my father and grandfather, I eventually learn to love it for all the things I could do on it, in it and all the blessings from it tht have sustained my family,” he said.

“How I felt about it is hard to explain. One thing was sure about wss that I could respect the ocean and everything in it. God created the world and everything in it.

The ocean has a purpose and we also have a purpose to protect it for ourselves and our future.”

When Cama asked Fuluna to accompany him to Yanuca in Beqa and deliver a camakau.

Fuluna agreed. It was the furthest he had sailed on one.

Over the years as the ocean became the only solace for the boy who grew up afriad of it, his love affair with it grew.

Then the Uto Ni Yalo was born. Based on the Polynesian vaka design for long-haul ocean voyaging, it was one seven built by German anthrolopologist Dieter Paulman, who saw one in the Cook Islands on a visit there.

Paulman was fascinated by the simple technology and the ancient skills that early seafarers had to determine their course as they travelled across the vast Pacific Ocean.

Paulman ordered the vaka built in New Zealand using modern material and contacted voyaging societies in the islands for crews to man the canoes.

As the plan unfolded, so too Fulana’s desire to face his fears out in the open on a vessel that looked like one from his father’s dream.

When the opportunity came, he joined the Pacific Voyagers in 2010 and the past was buried with his fears.

“I have learnt to put my worst fears behind me. aI learnt to undertand the nature of bondage with fear, which had become a curse on us.

“What my father did was wrong. I have learnt from it to understaand my culture and traditions better. to understand traditional sailing and that is not isolated from our way of life as islanders. They are inter-related. Our land, our ocean and our traditions, they have mana and we must always respect that which God has given. It is our identity.”

Fuluna rebuked the curse of his family when the Pacific Voyagers set sail, defying the odds across 50,000 kilometres through the Pacific Islands, all the way to the Americas,

Under the guidance of traditiotinal navigators from the Cook Islands who were part of the 120-crew during the voyage, he gained insight into how his ancestors navigated from island to island without the use of the compass and modern navigational equipment.

Relying only on the pattern of the wave and understanding the power of the wind, the fleet of canoes sailed from country to country, trekking cross distances that their ancestors had once undertaken.

Fuluna was one of three Uto Ni Yalo crew that received training under Tua Pittman, one of two master navigators from the Cook Islands who sailed with the Pacific Voyagers.

Pitman was a student of Mau Piailug who, in 1976, made international headlines when – using nothing but nature’s clues and the lessons he’d learned from his grandfather, a master navigator schooled in traditional Micronesian wayfaring – he steered a traditional sailing canoe, the Hokulea, more than 4828km from Hawaii to Tahiti.

Pitman was part of the journey, a project of the Honolulu-based Polynesian Voyaging Society, which was co-founded by anthropologists interested in the enduring mystery of how the Pacific’s scattered islands, often separated by hundreds of miles of water, had become populated by peoples who lacked nautical technologies such as the compass and sextant.

Piailug broke with tradition to share among other cultures his closely guarded navigation secrets that had traditionally been passed down only within families.

Among his students were Nainoa Thompson, a Hawaiian who became a master navigator, has many students and has completed long ocean-crossings; and Steve Thomas, a California native who made a documentary and wrote a 1987 book (The Last Navigator) about the months he spent learning from Piailug in Micronesia, and Pitman.

Pitman passed on his knowledge to the young Pacific Voyagers and Fuluna became an eager student, learning the names of the different stars that are used by navigators in wayfinding at night.

Piailug, who died at 78 on the western Pacific island of Satawal in Micronesia where he was born while the Voyagers were on their way to the Americas, was regarded one of the last masters of the nearly lost traditional art of using stars, sun and wind to find safe passage across the ocean.

Fuluna said he was blessed to have crossed Pitman’s path.

“I believe that fate brought me back to the ocean after I lost my father and grandfather to it. Fate brought me to te Pacific Voyagers and the training that Mau had passed on. Tua taught me well and I owe what I know to the Pacific Voyagers and the men who passed on their wayfinding skills.

For them to pass on that knowledge means that my children can grow up and know how to sail across the ocean before us one day.

For Fuluna, bringing home that knowledge and passing them on is the best tribute he could give Piailug, his father, Paki and the Pacific Voyagers.

SAILORS FROM ‘WAY BACK’ RESURRECT ANCIENT CANOE TECHNOLOGY

FROM the shade of the mangroves at Korova on the tip of the Suva peninsula where Jim Funaki once waited in vain for his father and grandfather to return home, the sight of the I Vola Siga Vou brings bitter-sweet memories.

The pain of his losing his father Metuisela Biuvakaloloma at sea while sailing his new canoe from Lau to Suva in 1993 and grandfather Jimione Paki on another in 2006 in his bid to start a tourism cruise business in the harbour of Fiji’s capital changed his heart about the ocean his life revolved around.

Paki, who arrived in Suva from Moce, Lau, in the East of the Fiji archipelago in1991 to resettle his family in the urban drift from the islands to development and better education and give his children a better life, was never seen again when he set sail from Ogea 350km away on the gifted saucoko drua his wife’s people, whom he regarded as expert craftsmen, built .

His dream to start a cruise business to cater for the growing number of tourists who disembarked from cruise liners for some Fiji cultural experience ended with his disappearance.

No one knows what happened to him. Only that he shared the fate of his son when he defied traditional protocol not to sail in waters declared taboo as a sign of respect for the fallen paramount chief of the Tovata confederacy of which Lau is a part of.

All that anger and hurt was buried in renewed awe and passion for the ocean when the Uto Ni Yalo was born.

It gave him the chance to reconnect with the ocean and the culture his grandfather had died trying to save.

Paki’s dream of the drua died with him and his kin at Korova did not attempt to build another drua.

Their only reminder of the grand plan were buildings skills of the camakau and bakanawa, small model canoes that children used for racing.

The Uto ni Yalo, part of a fleet of modern Polynesian vaka moana canoes funded by German anthropologist Dieter Paulman that twice crossed the Pacific to the Americas and back advocating for ocean conservation and sustainable sea transportation.

It allowed Funaki to cross paths with traditional voyagers and fellow Lauans Kaiafa Ledua and master navigators from across the Pacific

That encounter became a special training on celestial navigation.

When the I Vola Siga Vou, a canoe built on the design of the only Fijian drua that sits in the Fiji Museum, the Ratu Finau, built in 1904, and with the backing of sustainable sea transportation expert Dr Pete Nuttal, that training was put to use and an ancient war canoe came alive.

Once the pride of the islands in Lau, the major shipbuilding and sailing centre recognised across the Pacific for its fine craftsmanship, knowledge of the traditional drua culture is fragile with the descendants of the mataisau (traditional Fijian builders) and lemaki (Samoan specialist craftsmen brought to Lau in the late 1800s) in old age.

The threat of losing information held by the children and grandchildren of the mataisau and lemaki who built some of Fiji’s great drua fleets spurred renewed interest in reviving Fiji’s sailing heritage.

Dr Nuttal recognised this and with the help of then president of the Fiji Islands Voyaging Society (Uto Ni Yalo Trust) president Colin Philp, fellow geographer Alison Newell and traditional voyagers Kaiafa Ledua and Peni Vunaki, they conducted a research in 2011 to collect, collate and archive existing knowledge of the drua with funding from the University of the South Pacific’s Oceania Centre for Arts, Culture and Pacific Studies.

The research — titled The Drua Files: A report on the Collection and Recording of Cultural Knowledge of Drua and Associated Culture — was presented to the Ministry of iTaukei in 2012 which now holds it in trust.

It was the first time such an exercise had been attempted since the work of acclaimed anthropologist Laura Thompson in 1940 and the report’s authors believe it was also the first time such a data collection exercise has been undertaken by Lauans in their own dialect.

Ledua, who hails from Nayau in Lau, said the drua was the most important treasure the people of Fiji had to restore.

In 1982, during celebrations to mark the Year of the Indigenous People, the Fiji Government, on the request of the Auckland Maritime Museum, commissioned and funded the building of a drua by the Pacific Habour Cultural Centre.

A team which included Taniela Bese, the chief of Fulaga in Lau – whose recollections of the grand designs of the different drua were included in the 1991 research – built the Donu Mata, which is now stored at the museum.

In 1985, Bese was part of a team that used ancient tools, including a stone axe to build another canoe, Nai Matai, which was used during celebrations to welcome Pope John Paul II when he visited Fiji the following year.

According to the findings of the 1991 research, no great drua of the tabetebete design (multi-planked vessels sewn to a scarfed keel and of considerably greater size than the saucoko, drua and camakau built using a single large hollowed log as its base component) has been built in living memory.

Ledua said the building of the giant war canoes phased out when Christianity arrived in Lau in 1935.

Early missionaries opposed the building of the war drua because of the brutal ceremonies involved in almost every phase of the construction.

Human sacrifice was involved from the time a tree was identified in the jungle to the time the canoe was pulled into the water on human rollers.

“The belief was that it was necessary to ensure fair winds when the drua sailed,” he said.

In an interview with this magazine before his death three years ago, Bese said Fijians must work harder to restore their lost canoe-building and sailing skills

Thanks to Dr Nuttal that that technology is how the I Vola Siga Vou came to be. Based on the Ratu Finau, the builders modified it to include details of the tabetebete.

Using planks lashed together, the I Vola Siga Vou today sails with pride promoting sustainable sea transportation while providing a cruise service for tourists in the harbour.

Ledua said abot 200 planks were used to lash the canoe together.

With the wayfinding skills shared by the students of Micronesian master navigator Mau Pialug with Ledua, who is now part of the crew, the drua’s ancient technology powers the I Vola Siga Vou as it captivates visitors to Suva.

Paki’s dream is now the attraction of the Drua Experience, which operates in the same waters that inspired his business dream.

Only this one’s better. Through the I Vola Siga Vou, Fiji will never lose its ancient technology again.

Since February, the Drua Experience has been conducting sailing classes for students living in Suva.

With funding from the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Ministry of Education, students are taken through the whole process of canoe building, from identifying the right tree to the last stage when it is in the water and how to sail it.

“Our people now have the chance to walk in the footsteps of our forefathers and sail like they did,” said Ledua.

The drua’s sail design is regarded as one of the most efficient in the world that creates more lift like that of an aeroplane wing.

Compared to modern yachts which have a sideways effect, the drua is low-lying in the water and the energy collected from a small point is on the sail is channeled and gives the craft maximum power in full flight.

“We teach the children all that they need to know. From the type of tree used to how the hulls are hollowed out up to the the lashings and all the different knots that sailors use and all the technological advantages.”

The Drua Experience plans to build two bigger vessels .

“We have built the first and tested it. Now we know and can do a bigger one that can carry more passengers.

“The Tabetebete of old used to carry hundreds of people,” Ledua said. “We want to build something that portrays the skills

Manoa Rasigatale, one of Fiji’s advocates for the revival of traditional and cultural arts who named the Uto ni Yalo and sailed on her maiden voyage in 2010, said the drua was the icon of Fijian maritime and the revival of traditional sailing and canoe building would ensure Fiji’s future.

“The drua is the most solidly built, the most durable that can last five to eight years whilst in use and the fastest in all.”

“Traditional sailing skills is alive and will not disappear into the horizon like it once did.”

Paki and Bese are no more but the drua is here to stay.

——

This story was produced by Ilaitia Turagabeci, one of the participants of the climate change media workshop that Internews’ Earth Journalism Network facilitated with SPREP and the COP 23 Presidency Secretariat. This serves as a background to the field visit of the journalists and communications officers as part of the workshop held in Suva, Fiji last July 24-25, 2018. This story is originally posted at Islands Business (March 2018).