Nicknamed “the island closest to paradise,” Ouvéa is considered one of the most beautiful atolls in the Pacific. Part of the lagoons of New Caledonia, it was registered in 2008 as a World Heritage Site under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Its exceptional biodiversity, long preserved by a way of life rooted in the Kanak tradition, is now threatened by climate change. Rising waters are accelerating coastal erosion, imperiling habitats and forcing entire communities to change how they organize themselves culturally.

“When I was 12 years old, the seaside was further away, the beach was very wide, we could walk freely in large groups, there were big processions. Today, we would have to walk in single file on the road,” says Carolo Poueta, 68, as he points toward the small white stretch of sand between the turquoise lagoon and a row of ironwood.

Poueta is spokesman of the Heo chiefdom, one of six tribes of the district of Saint-Joseph in the north of Ouvéa. His house is on the other side of the coastal road, about 50 meters from the beach.

“We see a lot of changes,” Poueta says. “In the past, there were bike races, horse races happening on the beach. But now the water has won, the coconut trees have fallen to the ground.”

Coastal erosion is accelerating

Populated by nearly 3,400 inhabitants, Ouvéa’s highest point is 43 meters above sea level and draws a narrow crescent of land nearly 50 kilometers long and no wider than six kilometers.

The fact that coastal erosion is affecting Saint-Joseph’s shoreline is not new. Construction and sand removal that affected natural sedimentary drift have contributed to the problem. Since the 1970s, rising water has been threatening Takedji district, and a dam was built with blocks of coral to reinforce the sand embankments being nibbled at by the waves. It’s unclear how much longer the reinforcement work will endure.

Ouvéa goes up, but at a slower pace than water

Rising waters are a result of global warming. Largely caused by the phenomenon of thermal expansion – warmer water expands – the rise is not uniform around the surface of the globe.

“Relevant trends can be calculated over 40 years and show an acceleration in the speed of sea level rise in Noumea, which increased from 0.5 millimeters (mm) per year between 1957 and 1997 and 1.9 mm per year between 1977 and 2017,” according to Jérôme Aucan, an oceanographer from the Research Institute for Development (IRD) in New Caledonia.

At the same time, the continental mass is also moving. While some islands are sinking, Ouvéa is actually rising.

“Ouvéa goes up, but at a slower pace than the water,” residents say.

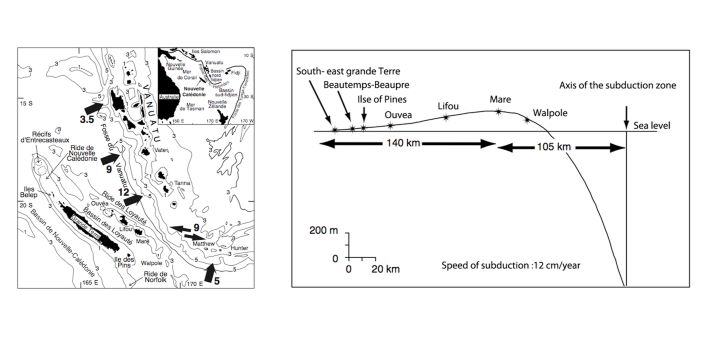

Bernard Pelletier, geologist and director of research at IRD, confirms that belief. Located on Loyalty Ridge, Ouvea is carried by the Australian tectonic plate, which rises on a bulge before diving under the volcanic arc of Vanuatu.

“The Loyalty Islands and the Isle of Pines have risen at the speed of about 0.12 to 0.25 mm per year,” according to Pelletier’s research. That rate of rise is less than the rising sea level.

If my country must sink, I sink along with it

“Coastal erosion and rising sea levels are not the only stressors affecting this remote part of the world,” says Pelletier, referring to tsunamis. In the Loyalty Islands, the last deadly tidal wave happened in 1875. Caused by a strong earthquake in southern Vanuatu, it killed 25 people on neighboring Lifou Island.

Even though the last tidal wave occurred more than two centuries ago, Pelletier says the threat of another remains.

“An event comparable to that of 1875 can happen tomorrow, in a month, a year or ten,” he warns. “What is certain is that it will happen, and we are already in the period when it can.”

Resident Jérôme Toulanguy, 53, says education can and should play a role in raising awareness.

“It is necessary to condition the young people about those issues, to explain what is happening.”

Carolo Poueta of the Heo chiefdom agrees that passing a message to the younger generation is important. But whatever the danger, he adds, he’s not going anywhere.

“I won’t leave. If my country has to sink, I sink with it.”

Will traditional values be lost?

At the core of the Kanak community, lies a relationship that has been built around the land. The erosion of the land as a result of climate change threatens to displace seaside tribes and disrupt their social fabric.

“This land has duties towards the chieftaincy,” Poueta says. “Each parcel of land has a duty, a job, a little like [when] some cobblestones [are] assembled — when all the cobblestones are together, the chieftaincy is complete, otherwise there is a hole in the system. If I have to change location, how can I continue to perform my duties and carry out my responsibilities to the chieftaincy? Will we lose our values? I do not have the answer.”

We must discuss

“With each blow from the west [which brings strong and sudden westerly winds] the erosion accelerates,” Toulanguy says. Rather than wait for a devastating cyclone or tsunami, “I choose to anticipate,” he says.

Toulanguy built his home inland, in part because it’s also the land of his clan. Many residents here do not have that option.

“In Takedji, people cannot go further inland,” says Alibi Ouaiegnepe, deputy mayor in charge of the environment. “Behind the houses, there are tappers and other houses, then other clans, other chieftains.

“We must discuss,” Ouaiegnepe adds.

The discussion will be long, according to Kanak culture, which gives rise to a customary decision. But the time for dialogue has yet to be set.

“Young people are attached to the speech of the eldest,” says Ouaiegnepe. “Old people should change their way of talking about the future. We can continue to live with our customs but we must plan ahead. The water will go wherever it wants.”

Mobilizing knowledge

To gain a better understanding of the risks, communities and institutions are mobilizing.

“There has been an awareness for a decade,” says Myriam Vendé-Leclerc, a geomatics geologist at the Department of Mines, Industry and Energy (DIMENC) with the government of New Caledonia. She’s working to take that awareness to the next level.

“The goal is to communicate with each other, to acquire and share knowledge, to provide decision makers with elements of understanding on the phenomenon of erosion,” Vendé-Leclerc says.

In 2012, as part of Ouvéa’s management plan, the Loyalty Islands Province organized workshops with different tribes to collect information on the residents’ environmental priorities.

“Erosion came first on the top-10 list of concerns,” says Luen Lopue, the province’s Biodiversity Studies Officer and World Heritage Manager.

The following year, Ouvéa became one of the pilot sites of the European project INTEGRE (Initiatives of the Territories for the Regional Management of the Environment) focused on integrating coastal-zone management. The project was implemented by the Pacific Community (SPC) and funded by the European Union.

INTEGRE brought together researchers and community representatives around several projects aimed at enhancing Ouvea’s natural heritage, managing threats and increasing the resilience of the population using a participatory management approach.

Dialogue is indispensable

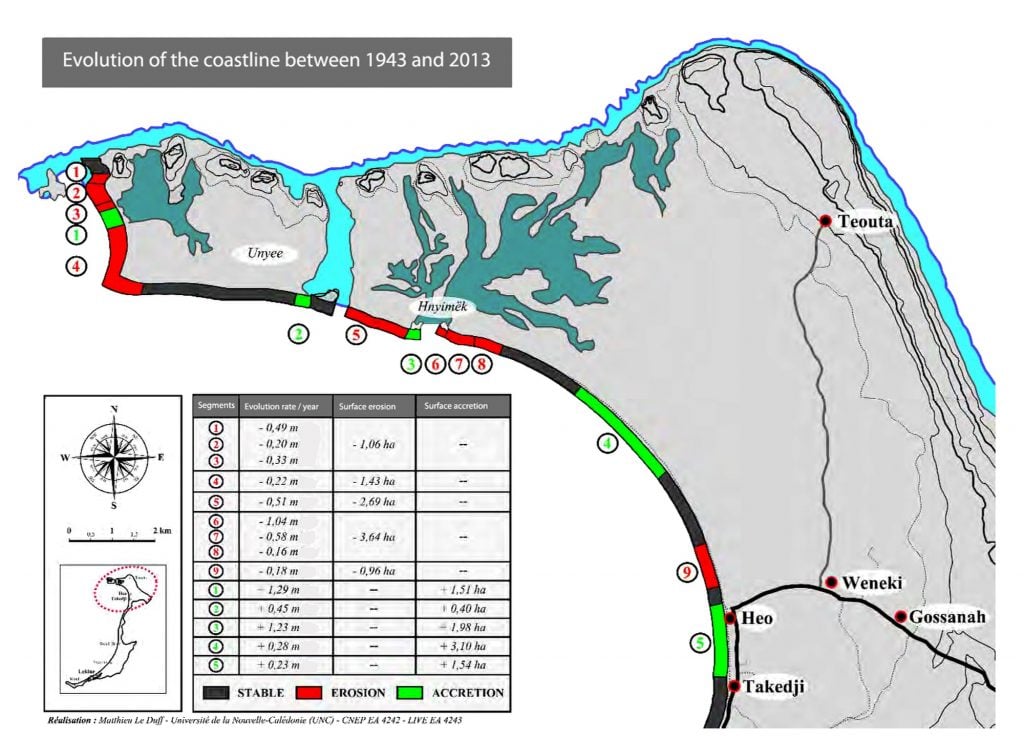

According to Matthieu Le Duff, a researcher at the University of New Caledonia, tools were provided to the wider population as well as decision-makers to understand coastal erosion. They were aided by quarterly measurements conducted by local associations.

Those efforts took into account the modes of representation and people’s way of life integrating those risks, Le Duff says.

“Dialogue is essential, and here in Ouvéa it’s even the first step,” he adds.

Through dialogue, residents today are more aware of the risks and play a part in the prevention process. Local associations mobilized within the framework of INTEGRE have worked effectively to raise awareness, especially among children.

A visit to Ouvéa in April 2015 by representatives of the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Fiji and Tuamotu, remains in the memory of many.

“In their islands, the situation is already critical,” Ouaiegnepe explains. “The water has entered inland, nothing grows, coconut trees die. In Ouvéa, erosion encroaches on the houses but not yet on the crops.”

Still, Ouvéa is endangered by the constant pounding of the waves. The municipality financed the construction of dams in Saint-Joseph and Lekiny, in the south of the island. But the technique used in Saint-Joseph is temporary. Nothing suggests that erosion will stop in the years to come.

Along the great chiefery wall of Takedjine a dike was constructed to protect Saint-Joseph from runoff and erosion. Photos: Aude-Emile Dorion

The water will come in, everything will be flooded

Further north no dam will be able to protect the mangroves. Ouaiegnepe points to the location of the tribe of Téouta, at the northernmost part of island, and the entire wetland that stretches between the west coast and the tribe.

“Here, in the back of Téouta, there is like a basin,” he says. “On this part of the island, the water will come in, everything will be flooded.”

Laurent Nassele, 61, lives in Téouta. “All the dunes are gone, he says. We feel threatened. If the water rises again, it is not the small embankment inexorably nibbled by the waves that will stop it. Today everything has changed completely, everything has become sand.”

Thinking with people

In Saint-Joseph, from the home of Carolo Poueta, the lagoon seems so peaceful. “We need outside opinions,” smiles Poueta. “Even if we see changes, we are in our daily lives. Those who don’t live here actually alert us to the scale of climate change.”

On the atoll of Ouvéa, scientists have handed over the reins to local organizations and groups in order to continue raising awareness on the fragility of the place.

But with the end of the INTEGRE project, the Loyalty Islands Province – which suffers, like all other Caledonian institutions, from budget restrictions – needs to seek other sources of funding.

LeDuff says that might result in a pause in some work. “But I am very confident about the pursuit of current activities,” he says. “All of these actions are going in the right direction.”

One necessity he insists on when it comes to averting disaster that doesn’t require money: “Try to think with people.”

This story was produced under the EJN Asia-Pacific Story Grants 2018 with the support of Sweden/SIDA.