Six years on from being appointed head of the Pacific Community, Director-General Collin Tukuitonga, a boy born on the tiny Pacific island of Niue, has a voice louder than a schoolboy rugby captain, a voice that serves him well as a Pasifika community leader.

There is little doubt his credentials are impressive for a boy who attended Niue High School and then the University of the South Pacific for foundation years 1 and 2 before arriving in New Zealand from Fiji after the 1987 coup.

Having done his New Zealand Medical Registration exams, he began to excel in the fields he chose.

And excel he did, as his curriculum vitae reads: Director of SPC’s Public Health Division; Chief Executive Officer of the NZ Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs; Associate Professor of Public Health and Head of Pacific and International Health at the University of Auckland; Director of Public Health, NZ Ministry of Health; and Head of Surveillance and Prevention of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases at the World Health Organisation, Switzerland.

He scoffs at the description of a little boy from Niue who has made it big in the Anglo-Saxon, neoliberal, covid-19 world of today.

“I don’t know about making it big, but it has been definitely different and professionally rewarding, and hopefully I’m making a useful contribution to the community,” he laughs heartily in the Pacific way.

But his contribution to all aspects of leadership in medicine and public service cannot be taken lightly.

‘No holds barred’

As Fijian Dr. Api Talemaitoga, a GP in South Auckland and chair of the Pasifika GP Network who is also part of the Health Ministry’s Pasifika response and who worked with Tukuitonga during the H1N1 flu epidemic in 2009, says:

“He is great because he tells you like it is, no holds barred, no sugar coating the truth,” he says of Dr Tukuitonga.

The fact that Dr Tukuitonga spoke out during the current pandemic crisis, calling for a new public health agency is evidence enough of this.

“Sars and H1N1 were epidemics but covid-19 is a much bigger threat. We can be certain there will be viruses like this in the future,” says Dr Tukuitonga.

“Even if this pandemic settles down it doesn’t protect us from something else coming along. So, it’s always going be a risk for communities right around the world.”

However, while he credits establishing Pacific public health services in West Auckland and the poorer Māori communities in Northland (Ngati Hine and the Hokianga) as deeply satisfying, it is his work as director-general of the Pacific Community (SPC) based in Noumea, New Caledonia, that is the cream of his public service to the Pacific.

But it was fraught with difficulties, which he found a surprise.

Fragile unity in the Pacific

“Being appointed Director-General of the Pacific Community (SPC) and running that organisation for six years was a highlight in my life,” he says.

But, “I learnt just how fragile unity is in the Pacific,” he says this with surprise.

“People talk about regionalism in the Pacific all the time and it is something people seek and desire but that actually is very difficult, elusive and fragile.

“Pacific regionalism and Pacific solidarity come with conditions, there is quite a level of distrust that exists and that’s holding back so many developments,” he says.

“But there are some good things going on – their collective approach to climate change has been impressive.

“Leading up to the 2015 Paris Agreement globally, nobody gave the Pacific a chance, but they banded together, and influenced some big players and got a good outcome in the form of the Paris agreement.

“The voices of the small Pacific Islands were heard at a global level that wasn’t because of chance. It came from the work of the Pacific Island leaders in communicating their concerns about climate change to the rest of the world,” he says.

Trying to push the polluters

“They were trying to push the polluters of the world to take responsibility for some of the things they had done.”

He praised the work done by Pacific leaders at a time when disunity could have been damaging.

“I do think they have done a tremendous job on climate change so that is an illustration of the Island nations having one enemy in common. Otherwise working together on regional issues is not so straight forward.

But it was considered better in the nation of his origins, he says.

“Niue is fortunate in the sense that if you talk about sea-level rise it is not an really an issue for Niue, but in term of the parts of climate change like killing coral and ocean acidification leading to coral bleaching they do affect Niue.

“They also feel the impacts of severe weather events like severe cyclones like everyone else around the Pacific.

“It is fortunate in that it is a high island and they don’t suffer from the sea-level rise parts but clearly they are vulnerable as everyone else with regards to climate change effects,” he says pensively.

Tokelau also at risk

However, Tokelau, as well as Kiribati, is also at a risk, says Dr Talemaitoga,

“When I visited there several years ago, the king tides were really something to see, the effects of climate change were starting to affect them then,” he says.

As for the heavy polluters, Dr Tukuitonga has a slightly different take on those countries,

“The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is in fact one of the important parts of the Paris agreement.

“That is why we spent quite a lot of time setting up the office in Suva to allow and enable the members to rethink and develop and introduce meaningful contributions

“So, I see it as a very important part of the implementation of the Paris agreement. But, like a lot of things, some countries take it seriously and some don’t,” he says.

And the impacts of covid-19 on climate change?

Covid-19 ‘an aggravation’

“In a sense, covid-19 is an aggravation because it would introduce health risks, limit movement of people and their ability to do things, such as their ability to try to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

“I see covid-19 as an additional challenge for the small islands to face on of top climate change,” he says.

The Pacific environment will also be vulnerable to climate change he believes.

Coupled by pollution and various other practices such as overfishing and over-consumption has had an effect, he says.

“The combination of climate change, pollution, population growth, and the exploitation of the environment is a serious threat to the sustainability of the Pacific environment,” he expounds.

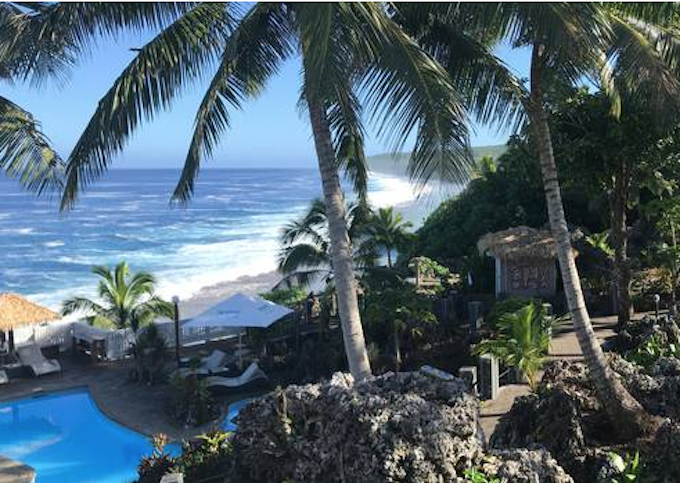

“There is a very strong drive to build more hotels in pristine places around the region because the drive for economic development is relentless and that leads to the destruction of our natural environment, so I do think it is a serious concern,” he says about the proliferation of tourist hotels in the region.

“The Pacific Ocean is increasingly polluted by actually pollution from outside the region but also the sea life is being threatened with overfishing and with ocean acidification as a result of that overfishing.

Pollution getting worse

“It will get worse; it has started already. That’s why the UN sustainable development goals are really important because one of those is dedicated to the protection of the health of the ocean.

“It’s already underway and I think we clearly need to do more within the context of climate change to protect and promote the environment around the region.

The same care should be taken when it comes to wildlife in the region.

“Sustaining wildlife goes hand-in-hand with environmental degradation so whatever we do to promote and protect biodiversity should, in fact, look to protecting the few species of wildlife that we have,” he says.

“Most of the small atoll nations in the world have very limited diversity, except the Pacific Ocean is one of the world’s largest ecosystems with quite a lot of biodiversity, some of which we don’t know about yet,” Dr Tukuitonga says.

“I have always been a fan of ecotourism and for travellers who spend a bit more money than the average person. I have never been a fan of bums on seats tourism and especially to little places. Ecotourism is a very important part of development landscape in the region,” he says.

He for one warned against the complacency that has taken hold in the Pacific with regards to covid-19. As a public health specialist, he notices how lax the testing had become in June and warned against that practice publicly.

Complacency factor

“I would have thought testing should have continued in earnest, without a doubt I think complacency is a factor and we should have done more testing,” he says in a few words.

After being 102 days covid-19 free in New Zealand, he used to be keen on the travel bubble to the covid free islands – but no longer.

“I was a keen promoter of that idea, but I would suggest to them right away not to pursue this. I would say to stop it.

“The problem is we don’t know quite what the spread is like in New Zealand and people could go to the Cooks or Niue integrating the virus there, so even if you test for it before going there’s not a guarantee that people with the virus are travelling to the destination so I would discourage it.”

And he has a passion outside his “norm of life”, a heartfelt one at that too.

“I’m very concerned about the Niue language because it is one of the realm languages that is in dire straits because very few Niueans speak it now and there is a very real chance that it will disappear completely.

“I’m part of a community effort to try to revitalise the language to have the young ones to speak the language.

Good health numbers

“It isn’t so bad around Fiji, Samoa, Tonga because there are good healthy numbers still living in those islands but the Cooks, Niue and Tokelau where the majority population are in New Zealand they don’t speak their first language it’s a real concern.

“I believe that absolutely that it is likely to affect their cultural behaviour because language is such a central and critical part of the culture and so while you can participate in your culture without speaking the language it is not the same as being able to speak the language which allow you to participate more fully,” he says.

“So, remember each generation of Cook Islanders and Niueans born in New Zealand would be further and further away from their culture so it is going to be a challenge to maintain,”

And that is likely to bring its own problems as Tonga found out recently.

“People feel disconnected from their social norms and traditional values, family connections are disturbed and of course that is almost an inevitable consequence that young people in particular would turn to drugs and crime. That is why I see languages as a protective element for our people,” he says with conviction.

He admits to being annoyed at not winning the World Health Organisation (WHO) regional director post for the Western Pacific last year when several Pacific nations showed themselves to be at the whim of foreign currencies.

“Only because I felt I had much to offer the Islands, also the Islands have never had a Pacific person in that leadership role, but life has moved on.”

Now the associate dean Pacific and associate professor at the University of Auckland, Dr Tukuitonga has been seconded to the Auckland Regional Public Health Service (ARPHS) one day a week and the service does the covid-19 contact tracing.

“I am happy to come back home and get involved in this. It’s good because it gives me a lot of freedom to explore the things that matter and I’m enjoying it.”