Expert says the best way to avoid climate justice issues in the Pacific region is to make sure that tuna habitats don’t shift.

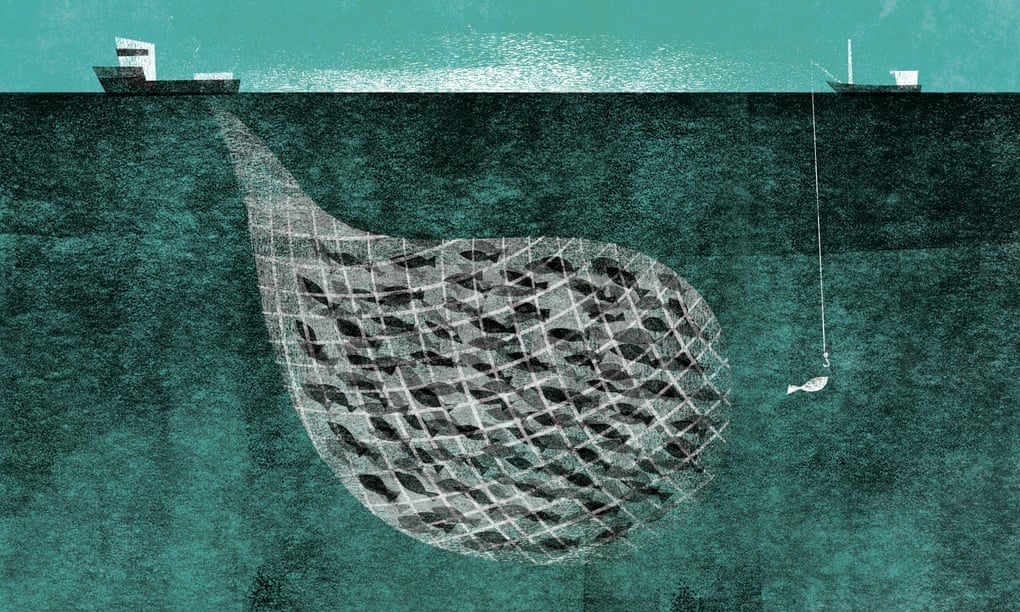

Despite their small size, Pacific Island nations and territories are a powerhouse in the fishing industry, contributing more than a third of the global tuna catch.

However, the tide could soon turn for these islands — and not for the better.

Fueled by greenhouse gas emissions, ocean warming will alter the habitats of tuna, causing these fish to move outside the jurisdictions — or Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) — of many Pacific Islands. Using modelling to predict how tuna stocks could move by 2050, a team of experts — led by Conservation International’s Johann Bell — found that an exodus of tuna could cut the average catch by a staggering 20 percent in 10 Pacific Island states, from Palau in the west to Kiribati in the east.

According to the study published today in Nature Sustainability, catch reductions of this magnitude could result in a collective loss of US$140 million per year by 2050 and cost some of these island nations and territories up to 17 percent of their annual government revenue.

“Currently, many of the tropical areas with warm waters preferred by skipjack, yellowfin and bigeye tuna are within the EEZs of Pacific Island states,” says Bell, who leads the tuna fisheries program at Conservation International.

“But as the ocean continues to warm, the conditions preferred by tuna will be located further to the east, including in the high seas, which are not governed by any one country.”

‘This is a climate justice issue’

Pacific Island territories are responsible for only a tiny fraction of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet they are already facing some of the most severe impacts of climate change.

“This is a climate justice issue,” says Bell. “Pacific Island states charge access fees to other countries that catch tuna in their jurisdictions. But as the tuna move progressively to high-seas areas the revenues will decline because less fishing will occur in their waters — and tuna-dependent economies will suffer.”

In contrast, large countries responsible for the majority of global emissions driving ocean warming will benefit from the migration of tuna, according to Bell.

“When the tuna are caught in high-seas areas, fishing fleets from wealthier countries can make more money from their catches because they do not currently have to pay fees to fish there,” he says.

Tuna fishing in the high seas of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean and in the Eastern Pacific Ocean is regulated by two regional fisheries management organisations. With insight from international lawyers, the study offers recommendations for a more equitable outcome: Pacific Island states could negotiate within these regional fisheries management organizations to retain the rights to the historical levels of catches made within their EEZs, regardless of the movement of fish to the high seas due to climate change. This would mean that although some tuna would no longer live within the EEZs of Pacific Islands states, their economic value would still belong to those nations and territories.

However, the best way to avoid this climate justice issue is to make sure that tuna habitats don’t shift in the first place, Bell says.

Cut carbon, save tuna-dependent economies

Under the Paris Climate Agreement, countries around the world have committed to drastically reducing their emissions to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

If countries are able to meet this goal, the average tuna catch in these 10 Pacific Island nations and territories will decrease by only 3 percent, the study’s authors estimate.

And with world leaders set to meet soon at a series of global climate negotiations, the onus is on large countries to commit to more ambitious emissions reduction targets and avoid climate injustice, says Bell.

“The climate-driven redistribution of tuna has the potential to severely disrupt the economies of developing island states and undermine the sustainable management of tuna resources,” Bell says. “Although we need more robust modeling to reduce uncertainty in the timing and extent of tuna redistribution, we are sounding the alarm on this potential economic disaster while there is still time to avoid it.”

This story was produced by Kiley Price, published at Conservation International on 29 July 2021, reposted via PACNEWS.