A new report recommends how law amendments could prevent statelessness and nationality loss for Pacific islanders who may be forced to migrate due to climate change

Kiribati-born Tiibea Baure moved to Australia in 2008 as a nursing student with a plan for her extended family’s future.

“So when one day they have to migrate due to climate change, I’m here, ready to take them on board,” the Toowoomba-based aged care service manager said.

But Baure said starting a life abroad came with its challenges.

When she arrived in Australia, she didn’t have access to Medicare or other social services and finding work for her husband — who arrived later — was difficult.

The 34-year-old permanent resident said the idea of Pacific Island nations having to consider the relocation of their people was never easy to think about but had to be planned for.

“It’s really hard to leave your country. We’re very connected to our land.

“It’s sad that over time our culture will disappear, or how we identify ourselves.”

The human rights, identity and dignity of Pacific islanders who may be forced to migrate due to climate change are at the heart of a report out today.

The Future of Nationality in the Pacific looks at how law amendments could prevent statelessness and nationality loss in the context of climate change.

Michelle Foster is the director of the Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness at Melbourne Law School and is one of the report’s authors.

“So the purpose of this report is to try to shed some light, to bring this issue to the attention of the global community and really to start a conversation around what sort of preventative action might be taken now, to ensure that statelessness does not result from climate-induced displacement.”

The report examined the nationality laws of 23 Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICT) to assess what existing risks may be present in legislation and the potential for additional risks as populations migrate.

Professor Foster said while migration was not the preferred option for PICT, it was one of the possibilities facing countries on the front lines of climate change.

Professor Foster said statelessness could expose someone to a life of discrimination and bar them from accessing an education, legal rights to work, vote, get married, or even open a bank account.

“So generally, statelessness is not just that a person feels that they don’t belong. In some legal sense, it actually has an enormously detrimental impact on their life,” she said.

“We’re also concerned about this loss of nationality, and that even if a person does have a legal right to live in a dignified way in a new country … the loss of their original nationality, could still have all sorts of implications for them both legally, socially [and] culturally.”

According to the report, under current citizenship laws, some Pacific islanders who leave their homes permanently are at risk of losing the citizenship of their home country, or the ability to pass this on to their children.

Some may even be at risk of statelessness and nationality loss even before they leave the country, the report said.

An example of this is the gender discrimination provisions in Kiribati’s citizenship laws that mean that only the father can pass on Kiribati citizenship to children born outside the country.

“One of the points we make in the report is … there are examples of countries that have laws that could potentially be right now contributing to statelessness, let alone if people need to move,” Professor Foster said.

“So that gender discrimination element is really important.”

The report makes 15 recommendations for amendments to laws for Pacific Island nations to consider, to ensure people don’t fall through legislative gaps and connection to their homeland can be retained.

“We’re making these suggestions with great humility, understanding that the states involved need to ultimately decide what is best for their own future,” Professor Foster said.

Among the recommendations is that Pacific Island nations could sign on to two UN Statelessness Conventions which sit at the heart of international human rights law.

“Very few states in the Pacific have actually ratified or signed on to those key treaties and so we suggest that that’s just a really good starting point because it gives those countries a framework for thinking about how their own laws may comply with minimum standards,” Professor Foster said.

The report also recommends amendments to nationality laws that remove discrimination based on gender and suggests putting legal safeguards in place to protect children at birth from becoming stateless, including when born overseas.

Additionally, the report recommends amending laws that could see people lose their nationality through living abroad.

“For example, even just voting in an external election, or even perhaps taking on a second citizenship may mean that you lose your nationality,” Professor Foster said.

“We’re recommending that consideration be given to revising nationality laws, and amending them to ensure that people don’t lose their citizenship in a way that is not really connected to national security.”

Allowing nationals living abroad to participate in overseas voting is also among the recommendations, as long as consideration is given to balancing the interests of those who still reside in the territory.

“More broadly, there’s clearly a need for countries like Australia and New Zealand to think through what displacement in our region may look like and how countries like Australia and New Zealand can work with Pacific states to find durable solutions for people that need may need to move because of climate-induced impacts in a way that upholds human dignity.”

This story was written by Edwina Seselja, originally published at ABC on 17 May 2022, reposted via PACNEWS.

-

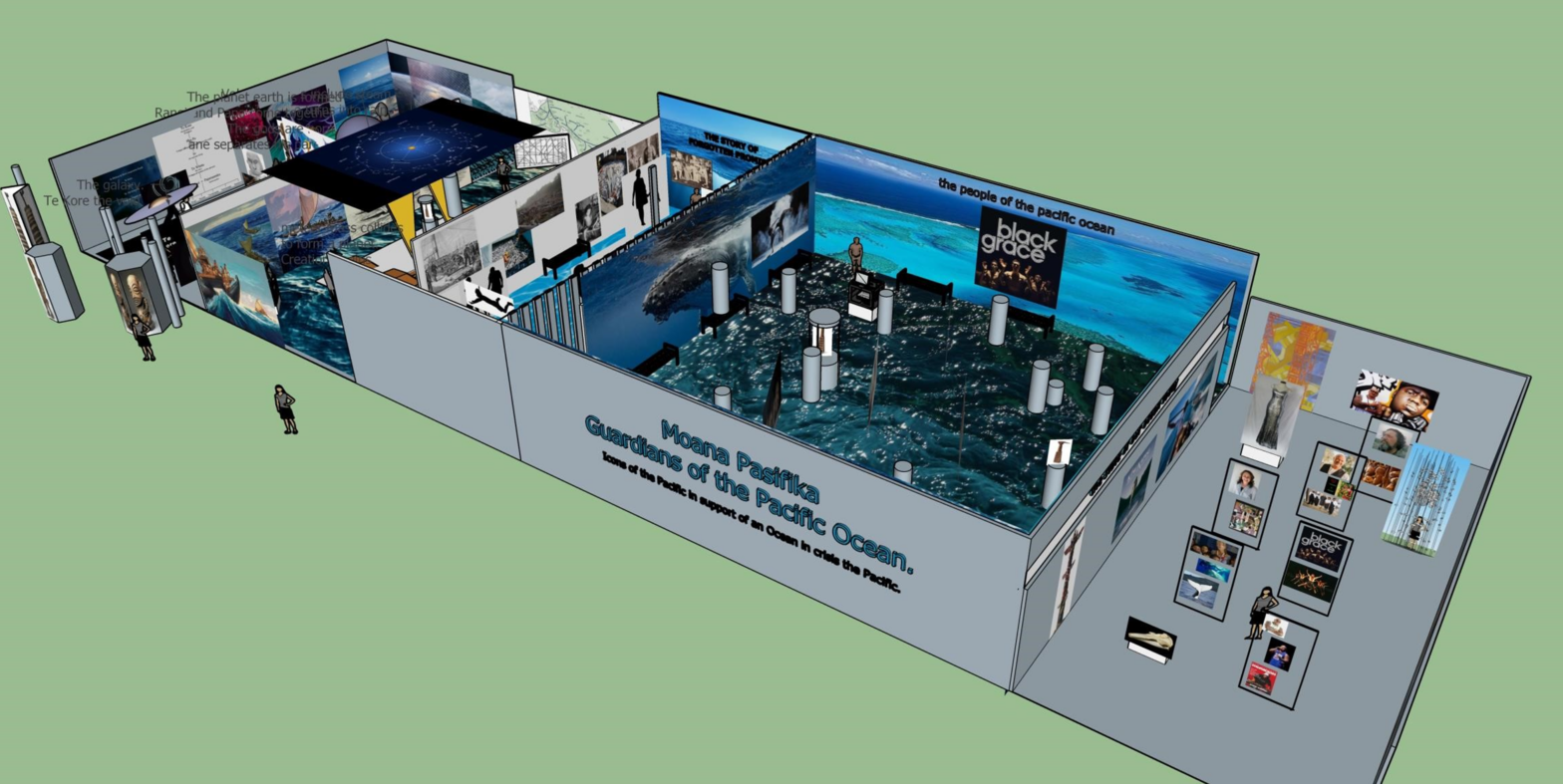

Tides of change: A journey to amplify the Pacific voices for ocean conservation

Stan Wolfgramm is working to launch the Moana Pasifika Global Touring Exhibition, aiming to amplify Pacific voices in ocean conservation through cultural storytelling and innovative technology to inspire global action