The eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai caused devastation across the Pacific Island nation that remains ongoing a year later

When ‘Eleni Via, 67, lived on the island of Atatā, her family were able to live off the land and the sea, surviving on crops planted in their garden and fresh seafood from the ocean.

But in the last year, life has changed dramatically. Now, they struggle in a new home, attempting to cultivate a land that is not as fertile as it should be. For the first time in her life, Via has to think about ways of paying the water and electricity bill, while making ends meet. On Atatā they could depend on fishing to provide basic necessities and for an income. In her new home on the country’s main island, Tongatapu, she wakes up everyday wondering how she will provide for her family.

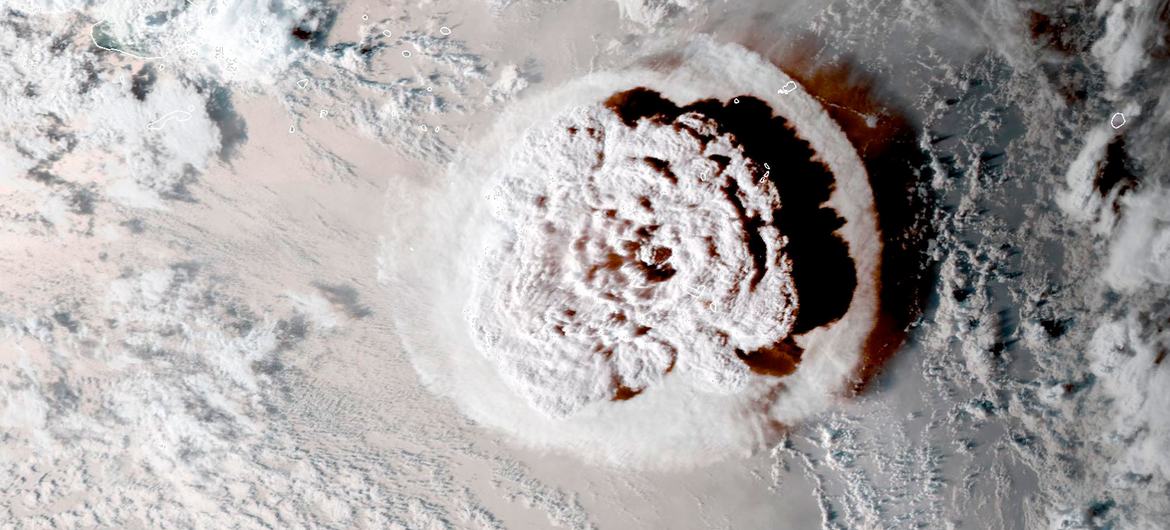

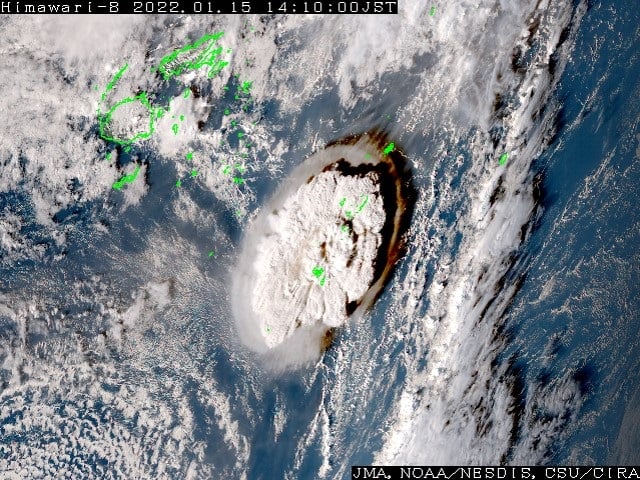

Like many Tongans, Via’s life was upended on 15 January 2022, when the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted. Satellite images showing the incredible size of the eruption were beamed across the globe, but as the eyes of the world turned to Tonga, the country disappeared. Damage to the undersea cable that supplies Tonga’s internet and much of its communication infrastructure meant that for days, the scale of the disaster was unknown.

When the government was finally able to communicate a statement, the news was devastating: the eruption had triggered a tsunami that overwhelmed a number of the country’s islands. 84 percent of Tonga’s population were affected by the tsunami or the volcano’s ash.

Residents who lost their homes were relocated to the main island of Tongatapu. The government called it an “unprecedented disaster.” The World Bank estimated the cost at US$90.4m – equivalent to 18.5 percent of Tonga’s GDP – most of this cost coming from the relocation and reconstruction of tsunami-affected villages.

Atatā was among the worst hit. The New Zealand Defence Force described the damage to the island as “catastrophic” and a UN assessment found dozens of structures had been damaged while the entire island was blanketed in ash.

A year on and Via, with her husband, Ma’uhe’ofa Via, and granddaughter, Tu’aloa, have finally left the home of the relatives they’d been staying with since the tsunami, and moved into a settlement of new houses in the village of Masilamea on Tongatapu.

“We are very happy to have settled here. Our island home has been ruined. We’re grateful for [what] we have been given … free of charge,” Via says.

The house has one bedroom, a bathroom and toilet, a veranda where all dining is done, and food is cooked on a fire outside. They have few utensils and plates. Via longs for a kitchen to make food and a place for storage.

Housing remains a problem across parts of the country, after many homes were damaged or destroyed by the tsunami.

On the other side of the island, in the village of Patangata, lives Mosese Sikulu Mafi, 61, whose family live opposite the sea and witnessed first-hand the devastation of the tsunami.

Despite widespread damage, in his community only six new homes have been built. The government promised ten, but even that won’t be enough according to Mafi.

“At present, there are a lot of houses that need to be rebuilt. The problem is that there is no equal distribution and the surveys that are done do not reflect the reality of the living circumstances.”

He suggests that in order to protect the people from another tsunami, the foreshores be built higher, and another emergency exit be provided.

“At the moment the only way out of Patangata is the road next to the ocean and we hope to have a back road that would take us directly inland in case of future tsunami emergencies.”

Mafi remains grateful though – his family still have the ocean at their disposal, which produces fish and seafood which they sell by the roadside. And despite the devastation, none of his community were killed in the tsunami.

“I’m just grateful that it happened during the day as if it had happened at night, there would have been a lot of children deaths,” he says.

“We lost everything. I don’t think anyone escaped the wrath of the tsunami.”

Few can escape its memories either. Mafi says that the last time there was an earthquake the national tsunami siren went off and everyone ran inland.

Many children have been particularly affected. Via’s granddaughter is just five, but lives in fear that a tsunami could happen again at any moment.

“When lightning and thunder occur, or there is strong winds and heavy rain, she turns to me, ‘is there going to be another tsunami?’ I tell her, ‘No. It’s just rain and strong winds.’”

Meanwhile, as Via puts it, “We place our trust in God yet again.

This story was written by Taina Kami Enoka, originally published at The Guardian on 14 Jnauary 2023, reposted via PACNEWS.