Palau’s president says it’s understandable why some Pacific countries would want to endorse mining ventures, “but sometimes, in the haste of making money, we could lose so much more” while calling for a halt on seabed mining until 2030

Palau President Surangel Whipps Junior said he wanted the seabed mining practice temporarily suspended until at least 2030.

“The ocean for us is life. We depend on it for sustenance, we depend on it for our economy – without it, we would not be able to survive,” he said.

“Whether they’re dredging it or clawing at the bottom and the plumes that would create, how would that affect our tuna fish stocks, the sharks, the most important resources that we have?

“It’s alarming, it’s reckless. As leaders and business leaders, don’t let greed lead to what could be the worst disaster that we could face.”

Whipps Junior said he understood why some Pacific countries would want to endorse mining ventures, “but sometimes, in the haste of making money, we could lose so much more”.

“I understand the economic realities that we all face, we’re battered with COVID, hit with climate change issues and we all need financing and maybe this is our ticket to solving our economic problems,” he said.

“That’s what we’re asking – let’s take time, let’s analyse, let’s use the best scientific data to make the best decision for our climate and for our people.”

As a crucial deadline looms for a new frontier of mining in the deep Pacific Ocean, Pacific Islanders are worried the controversial practice could go ahead before proper regulations are in place.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) will begin accepting applications for industrial-scale deep-sea mining in Pacific waters in July.

Cook Island resident Alanna Smith said any damage to ocean ecosystems would be devastating for her country, where the sea is central to life.

“I’ve always admired watching my aunties out on the reefs, getting seafood to bring home, so it’s provided for us,” she said.

Smith now works for an environmental NGO called Te Ipukarea Society, which advocates for protecting the ocean.

She said it was too early to consider deep-sea mining in the area.

“[It] is very concerning given there’s still a lot of data and research that has to be collected,” Smith said.

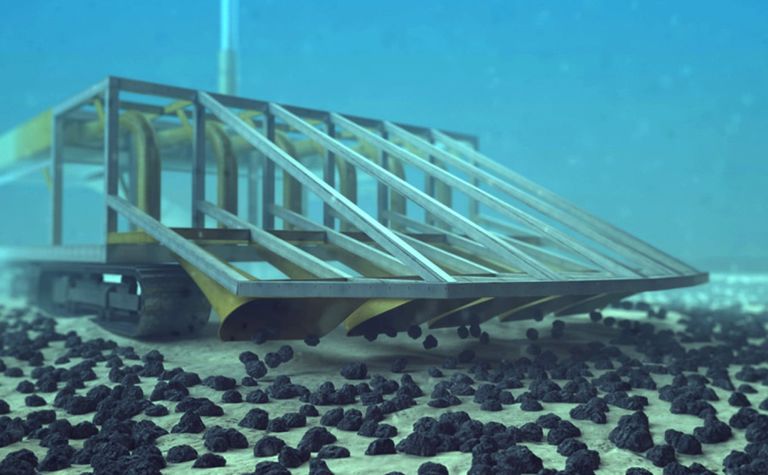

Deep-sea mining uses heavy machinery to harvest rock nodules from the ocean floor that contain cobalt, manganese, and other rare metal used in batteries.

It has never been done successfully on a commercial scale, but a new wave of interest in the materials, motivated by the expansion of renewable technologies, has been criticised by Pacific leaders who want bans, or stronger regulations put in place, until more is known about the environmental risks.

“We’re only really just scraping the surface of what damage is going to be caused,” Smith said.

The ISA, comprising 167 member states, has spent decades trying to develop rules and regulations for deep-sea mining but has still not finalised them.

In 2021, Nauru pushed the ISA to accelerate the adoption of regulations, after sponsoring an application by a Canadian company to mine for nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Zone – a part of the international seabed between Hawaii and Mexico.

It triggered a rule that stated that even if regulations had not been developed after two years, the ISA would still have to consider a commercial mining application.

The deadline is 09 July.

Dr Aline Jaeckel, an expert in international maritime law at the University of Wollongong, said it was unlikely this deadline would be met because negotiations with the ISA were still playing out.

“Some of those issues are to do with the financial, compliance and enforcement regime but also the fact the ISA has committed to create or develop environmental thresholds for seabed mining,” she said.

Genealogies, stories not considered

Last week, Smith travelled with the Te Ipukarea Society to Jamaica to attend an ISA meeting to discuss standards of the new practice with the UN body.

She said Pacific notions of underwater cultural heritage “hadn’t been tabled in the 28 years that the ISA meetings have been running”.

“For a majority of states these are tangible things like sunken artefacts but for the Pacific, there is a deeper connection where we have genealogies, stories, where our Atua (spirit) resided in the deep sea.

“There is this intangible connection that Pacific Islanders have to the deep sea.”

Dubbed a new frontier for mining, Smith said it was another form of neo-colonialism that would “take away a lot of that spirit and identity we have as Pacific Islanders”.

Her concerns were shared by fellow Maori and Cook Islander Liam Koka’ua, who is a senior Pasifika specialist with Auckland Council.

“There is potential to lose a whole lot of habitat for rare species that are found nowhere else on the planet … to have extinctions of species that are currently unknown to science,” he said.

“I believe that the interconnections [between] the deep seabed, up the water column to the surface, means whatever habitat or species loss might occur will affect important food sources for us as Pacific people.”

In previous interviews with the ABC, deep-sea mining companies disputed some of these claims and said they were undertaking rigorous research to understand its impacts.

The ABC asked the ISA to be interviewed for this story but did not receive a response.

Some countries like Palau, Vanuatu, Samoa and Fiji have called for a precautionary pause until more research is done, but others have seen it as a new revenue stream.

Cook Islands is pushing for it to go ahead – something Koka’ua is not happy about.

“We are very well off, we don’t really need that money,” he said.

He said Pacific countries should be “following a precautionary principle” and waiting to understand the impacts of deep-sea mining before giving it the green light.

Scientists like Professor Gavin Mudd from Melbourne’s RMIT University share the environmental activists’ concerns, and said other options needed to be explored first.

“I think we’ve got plenty of options for how to supply the metals we need from land so I think we should really be focusing on making sure we do that right,” he said.

“I don’t think we’ve really nailed how to monitor deep-sea mining, we don’t understand how likely restoration success is going to be with deep-sea mining.

“They’re still big long-term questions that have not been answered sufficiently,” said Mudd.

This story was written by Marian Faa, originally published at ABC Pacific on April 2023, reposted via PACNEWS.